How does North Korean media spread within foreign audience spheres?

When you think about ChatGPT, what emotions come to mind? Wonder? Excitement? Fear?

The recent surge in AI capabilities ignited journalists into a flurry of dialogue about AI’s potential and role in society. Universities scrambled to pass plagiarism rules and to reevaluate admission essays. Yet, while some are afraid of AI, we are generally excited at BARN OWL.

Authoritarian governments successfully run foreign language sites through state media, with security personnel failing to quickly identify their articles. North Korea is an example- their presence in foreign media is known, but the scope is undetermined. However, AI technology has the potential to change this if developed ethically and applied correctly. In this article, we go into how AI and human coders can support each other in the context of increased tensions between North Korea and the international sphere.

Introduction to Analysis

Last November, BARN OWL delivered a report on the avenues by which Iranian state media reached English-speaking audiences. At that time, civil unrest gripped the country as the government sought to quell mounting waves of criticism in the wake of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini’s death. We collected six articles published by Iranian state media using Ahrefs’ backlink tool and linked them to various websites and online communities responsible for dissemination across the internet. Next, we classified the responses from these websites and online groups as either agreeing with the article, disagreeing with it, or neither. This classification relied upon human judgment. Our analysis revealed which narratives and sentiments were more or less compelling to English speakers. We decided to modify our approach for this report from focusing on Iranian State Media to focusing on North Korean State Media in the wake of increasing tensions between North and South Korea. In doing so, we sought to tackle one of our previous report’s limitations: reliance on human judgment.

In this report, we investigate how North Korean state media reaches English-speaking and Korean-speaking audiences. We use pre-trained sentiment categorization models in place of human judgment to obtain positive or negative labels in addition to confidence scores on the probability of label prediction. We also look at the backlink profile of a subdomain on a state media website to find the sources of articles. Our methods section lists more modifications.

Context to North Korean Articles

Between December 31, 2022 and February 24, 2023, North Korea shot five short-range ballistic missiles and four Hwasal-2 strategic missiles around the Korean Peninsula and into the Pacific Ocean (BBC, CSIS, REU, REU). South Korea and the United States conducted air exercises before and after these missile launches. North Korean state media has long reported that joint drills between South Korea and the United States are preparations for an invasion (AP).

It is important to note that the war between North and South Korea never ended; there was an armistice, not a peace treaty. The armistice suspended open hostilities and created a demilitarized buffer zone between the two countries. In 2018 there was an Inter-Korean Summit in which North and South Korea officially agreed on the buffer zones and agreed to denuclearize (KOR). However, this was before the election of Yoon Suk-yeol. On March 24, 2022, before the election of Yoon Suk-yeol, North Korea shot an inter-ballistic missile for the first time since 2017. After the election, Yoon Suk-yeol made it clear that his priority was the step-by-step denuclearization of North Korea and enforcing sanctions. The strategy was a drastic change from the former president, whose number one priority was improving relations with North Korea (NYT).

Methods

Our approach to analyzing North Korean media is separated into three stages: Source Collection and Processing, Model Selection and Initialization, and Analysis. For Source Collection, we selected the English and Korean subdomains of the Korean Central News Agency (KCNA) (kcna.kp/en) as our target state media website.

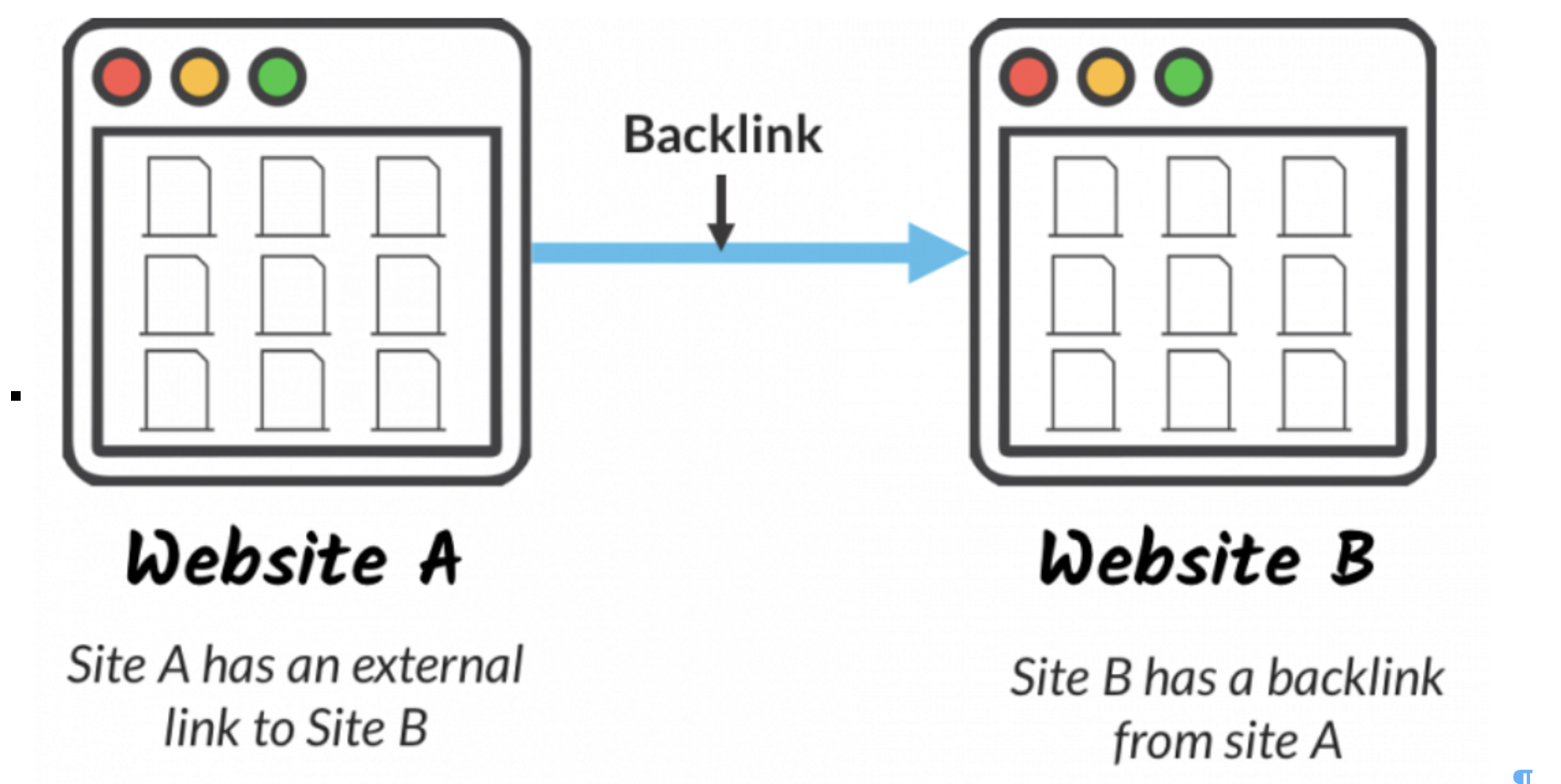

Figure 1 Backlink example from https://moz.com/learn/seo/backlinks

We input this link into the backlink profile tool on Ahrefs, allowing us to see how two websites link together. Then, we created separate searches for the keywords ‘missile’ and ‘Kim Jong Un’, which we believed would be contained within the anchor text of relevant copy related to the current tensions in the Korean Peninsula.

Our data collection window was between January 1, 2023 and February 26, 2023. We only considered DoFollow backlinks to textual sources written in English. In this report, we focused on domain-to-domain backlinks instead of individual user hyperlinks like in our previous report. We visited these sources and stored their headlines and content as plain text files.

Here we further diverge from our previous approach by using keywords to filter our search results. This improved our search by removing backlinks to irrelevant KCNA articles, such as links to content about North Korean culture or cuisine.

Our team selected a pre-trained language model available on HuggingFace to analyze the text files: DistilBERT base uncased fine tuned SST-2. This model can deliver sentiment labels and confidence scores for texts containing up to 512 tokens without fine-tuning.

Furthermore, we compared the algorithms’ classifications with our human judgment, effectively comparing two types of methodology – human judgment, which was the methodology for our previous project, and natural language processing, the chosen methodology for our current study.

Analysis

Dataset

Our dataset consists of 15 articles backlinking to the KCNA and their respective headlines. Seven articles contained the keyword ‘missile’ in the anchor/surrounding text of websites backlinking to the KCNA subdomain. These articles were posted and reposted a total of 44 times during the data collection window. Reposts contained identical text in all instances, save one wherein the article, containing many grammatical errors, appeared to be retranslated into English from a separate language using an automated translator. The articles provide coverage of recent missile launches supplemented with a brief analysis.

Eight articles contained the keyword ‘Kim Jong Un’ in the anchor/surrounding text of the websites backlinking to the KCNA subdomain. These articles varied in content and sentiment, which were posted and reposted a total of 27 times during the data collection window. They covered Kim Jong Un’s actions, personal life, and statements.

Figure 2 North Korea tests missiles (Source: KCNA via Reuters)

Missile

Our results show that for articles dealing with missiles, the sentiment classifier tool generally rated both the article text and the headlines as negative. For both articles and headlines, the classification distribution was five negative to two positive, showing that, on the surface, the ratings of both data points largely agreed. However, we found that the classification of the article and headline matched in only four instances. In the other four instances, the classification for the two data points did not match. For example, in a New York Post article about Kim Jong Un’s daughter’s attendance at a missile launch, the article itself was classified as negative while the headline was classified as positive.

‘Missile’ Keyword Sentiment Analysis

| Human, AI | Headlines | Articles |

| Positive | 1, 2 | 2, 2 |

| Negative | 6, 5 | 5, 5 |

The same trend was seen for human judgment as the results from the sentiment classification tool. We rated both the articles and the headlines to be majority negative. For the articles, we classified five articles as negative and two as positive. On the other hand, for the headlines, we classified six headlines to be negative and only one headline as positive.

Looking at how often the two classification sources matched, human judgment matched with the sentiment classifier for both the article and the headline for only three instances. Of the remaining five cases, in two instances only the classification for the headline matched, and in one case only the classification for the article matched. Finally, in two instances, human and tool classifications differed for both the headline and the article. We will discuss the implications of these findings in our discussion section.

Figure 3 Kim Jon Un with Daughter (Source: KCNA via Reuters)

Kim Jong Un

Compared to the articles on missiles, human coverage containing North Korean leader Kim Jong-Un was relatively mixed.

‘Kim Jong Un’ Keyword Sentiment Analysis

| Human, AI | Headlines | Articles |

| Positive | 3, 3 | 5, 5 |

| Negative | 5, 5 | 3, 3 |

The sentiment classifier argued that the coverage was relatively positive, showing five positive and three negative articles. However, this trend was flipped for the headlines, with the sentiment analysis AI showing three positive and five negative articles. This discrepancy suggests a high amount of disagreement between the two data points of the headline and the article itself.

The sentiment classifier and human judgment on this issue tended to disagree with each other as well. For example, we rated five articles as positive and three articles as negative with our own human judgment. However, the sentiment judgments differed with respect to which articles we rated as positive or negative. The same was seen for the headlines. Although we had rated three positive and five negative headlines, the sentiment judgement for headlines as positive or negative were different.

The two points of judgment matched for only three instances, and human judgment matched up with the sentiment classifier for both article and headline. Of the remaining five, only one matched when dealing with the headlines, and only one matched when dealing with the article. Finally, in two instances, our judgments for the articles and the headlines differed from the judgments made by the sentiment classifier tool.

Discussion

Coverage for ‘missile’ tended to be rated as more negative for both human and sentiment classification tool judgment, whereas coverage for Kim Jong Un was mixed with a positive slant. These differences between keywords may be because both Western and international media do not favorably cover missile launches. Kim Jong Un and his sister Kim Yo Jong have repeatedly criticized the international coverage of these launches, labeling them hyperbole as North Korea was just doing routine drills (as seen here). On the other hand, positive coverage of Kim Jong Un might reflect that he, as the leader of North Korea, is discussed in cases outside of warmongering.

What does it mean when algorithms and humans clash?

In many cases, human and algorithmic judgment did not match for our short exploratory foray into sentiment analysis. Two main implications can come from this disagreement.

One is that sentiment classifier judgment tends to be more objective, and human judgment more subjective.

For example, one of the articles we sampled was about Kim Yo Jong’s statement that North Korea would not fire missiles at Seoul. Among human coders, we regarded this as a good thing. However, the sentiment classifier tool regarded both the article and headline as negative. As we can see from this example, the use of a sentiment classifier may be useful in supplementing human judgments, which were, at the time, created from the fact that Kim Yo Jong’s statements were relatively tame. The classifier tool could be said to be effectively the voice of reason, casting doubt on human biases to point out that this is not a usually positive string of words put together if it were attached to another leader.

However, there were other cases where our human judgment was used to supplement the sentiment classifier tool. For example, in the article about Kim Jong Un signing holiday cards, we rated both the headline and the article as positive. However, the sentiment classifier tool judged both the headline and the article for this as negative.

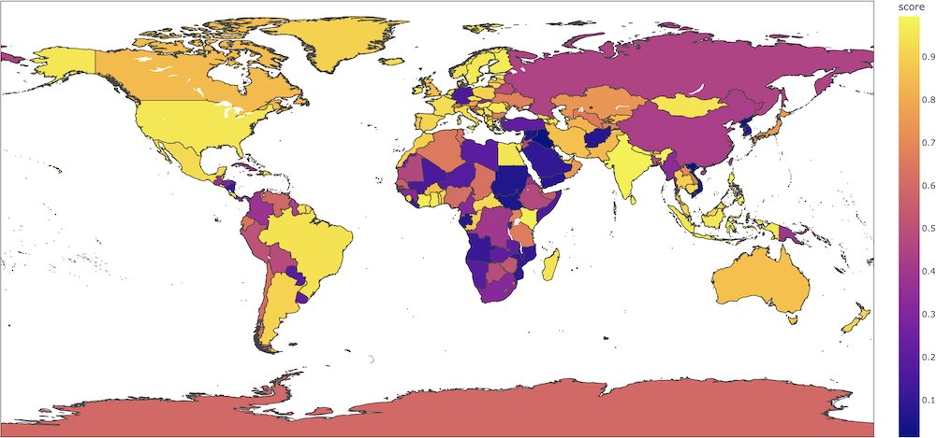

Figure 4 This map shows which countries are more or less likely to be judged as positive in the DistilBERT model.

(Credit: Aurélien Géron)

Of course, it may just be the classifier correcting human judgment again, but we believe it was human judgment supplementing the sentiment analysis tool. For example, in the limitations section of the English classifier we used, some areas of the world were underrepresented, thus leading to majority negative or positive evaluations despite there being no other indication that the sentence is like that. This result is due to the nature of the data that was used to train the classifier. As we can see on the map, all three countries that Kim Jong Un had written a New Year’s card to – Syria, Russia and China – are all rated less likely to be classified as positive, with Syria being the lowest at around 0.1 and China and Russia sitting at 0.3. Another interesting point is that both Koreas are rated around the same range as Syria, which indicates that these limitations may have pulled down the positivity ratings for most of our articles (as we are dealing with North Korea). In such cases, human judgment can be used to correct the biases of the tool used.

What does it mean when the article text and the headline clash?

In addition to human and algorithmic judgment clashing, the classification of the article and the headline sometimes did not match. For example, in the NY Post article about Kim Jong Un’s daughter, the headline was rated as positive, but the article itself was considered negative. What may have caused this mismatch between the two data sources is that because headlines are generally designed to help catch a person’s attention, they may exhibit a different sentiment than the one expressed in the article text. As a result, humans are drawn to novel and negative news, making us prone to disinformation and inflammatory articles.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

While the conclusion that human judgment can be used to aid algorithmic judgment or vice-versa is valuable, our research was not without its limitations. First, there is a limited sample size. As we sought only to analyze unique news websites (i.e., articles not copied from other sources), our total sample size was only 15, which may not be a representative sample of the entire coverage of North Korea. Furthermore, we could only analyze the first 512 words due to the limits of the classification tool, which further complicated our data. Future research would do well to analyze more articles in their entirety, perhaps splitting the text into 512-character blocks as suggested here.

Another limitation was our inability to analyze non-English sources, even though the coverage of these non-English languages may follow an interesting trend. North Korea operates Japanese- and Chinese-language propaganda sites. With Japanese and Chinese news sources, we could also access the KCNA website, providing more balanced, positive, or negative coverage of the North Korean situation. Future research would do well on how sentiment classification can work with human judgment for different languages.

Conclusion

In conclusion, through this short analysis, we find that human judgment can supplement those made by a sentiment classification tool and vice-versa, showing that sentiment analysis partnered with the SEO keyword data could be a valuable tool for future research. Furthermore, we find that coverage for certain issues is more negative than other issues. Although if this finding will hold for larger datasets and other languages remains to be seen. Although this small sampling of data and exploration of possibilities is limited, we hope this short essay may inspire further research on a larger dataset and a variety of languages so that the relative value of this approach can be more accurately judged. While it was a small case study, we hope that this begins to shine light on the possibility that AI and humans can work together in grayer areas like misinformation to avoid bias.