Introduction

Generative Artificial Intelligence (generative AI) took the world by storm with recent innovations like ChatGPT. Disinformation experts raised alarm bells in news articles such as this one from the New York Times about the potential for nefarious agents to use generative AI to effortlessly create disinformation and conspiracy theories in seconds.

However, we noticed that the article did not cover the threat of people using generative AI to check if an article is disinformation. The tool claims to increase productivity and help humans with mundane content, but can its guardrails and processing ability also be used to find reliable, unbiased content nuances signaling disinformation and alert the user?

Over the 2022-2023 academic year, the GDIL team BARN OWL (Behavioral Analysis of Related Networks of Open Web Links) studied website search engine optimization data for activity signals that might signify coordinated activity. We used our 200+ website dataset to play with the generative AI’s disinformation detection abilities. The dataset included neutral, satire, and disinformation sites in English, Korean, Arabic, Spanish, and Mandarin. Notably, we gathered the sites to study link structure without attention to the content beyond its believed category. Each student coded each website blindly as “neutral”, “satire”, and “disinformation”. However, even with the measures taken to assure blindness, human bias in website categorization still exists.

Could a tool like ChatGPT be used as an unbiased intercoder or even as an “arbiter of truth”?

Developed by OpenAI, ChatGPT works to engage users in a conversation by returning requests with responses built through data scraped across websites, articles, and public individual data up until September 2021. Notably, sites that included “hate speech, adult content, sites that primarily aggregate personal information, and spam” were left out of the dataset which can be a large subset of disinformation sites. Disinformation sites in our dataset may also be younger than September 202 crafted to prey on movements or fads that occurred after the data was scraped. Thus, ChatGPT could struggle with anchoring truth or detecting new hate terms, slang, and hashtags.

In light of this powerful tool taking the academic community by surprise and people’s fears in its easy fake news story creation, we wondered if AI could assist humans in identifying disinformation or be able to detect it itself. ChatGPT can summarize books and articles, so why not website homepages? This could save humans hours of time reading dozens of articles, often in foreign languages, to assess the reliability of news sources. The following research adds to our previous research about AI’s role in sentiment analysis and further tests ChatGPT’s ability to identify disinformation sites.

Methodology

BARN OWL used the term “gray sites” for sites that coders disagreed on categorization between “disinformation”, “neutral”, or “satire”. Note: BARN OWL used the term “disinformation” for a category liberally here. We built the database to categorize sites with the purpose of studying link structure, not content, and thus were not focused on assigning blame but instead simply on how information traveled. The Global Disinformation Lab, and BARN OWL, categorizes disinformation as false information knowingly spread and misinformation as information unknowingly spread.

We ran our site from the database through ChatGPT’s GPT-3.5 instead of ChatGPT 4.0 due to financial limitations. We split up large and small websites using their Domain Rating (DR), which is a metric from 0 – 100 that Google uses to determine how high a site will rank overall in its search results. The DR uses dozens of signals to calculate the score. The closer the rating is to 100, (Google is 98 while TikTok is 95), the higher they rank in search results.

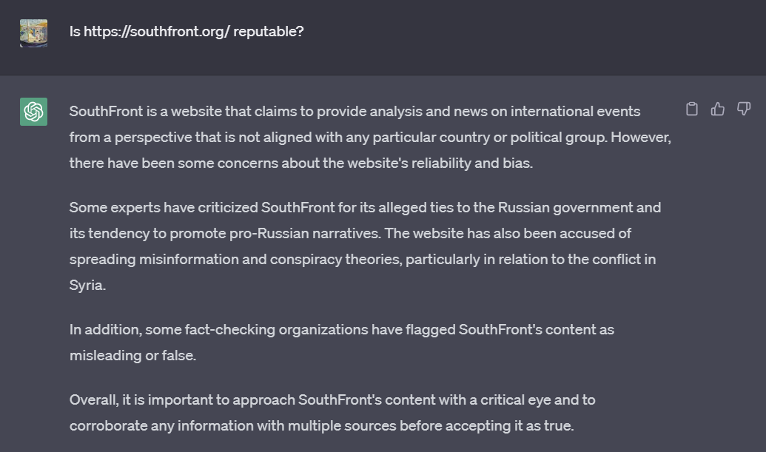

We classified websites with a DR over 60 as “big” and under 60 as “small”. We pulled from our database using a random number generator until we got 5 large neutral sites, 5 large disinformation sites, 5 small neutral sites, and 5 small disinformation sites. We entered each website into Chat GPT using the question, “Is (enter the website) reputable?” This allowed us to get an unbiased result and not have a leading question asking if it was a disinformation site or not. We recorded what Chat GPT said about each website and compared it to our human analysis.

Results

Most of the time, ChatGPT and our intercoder results agreed on a site’s category. The tool agreed with our database categorization on 19 out of 25 sites. For instance, when we ran The Epoch Times through ChatGPT, a site that we identified as disinformation, ChatGPT said that it “has been flagged by some fact-checking organizations for publishing misleading or false information” and “been linked to social media networks that spread disinformation.” ChatGPT largely agreed with our findings but also always put a disclaimer to consider the biases of the website and to cross-check information.

Our database categorization and ChatGPT disagreed on six site. sFor five of those sites, three were small neutral sites, one was a big neutral site, and one was a gray site. ChatGPT responded similarly to these as to The Epoch Times case, stating:

- It is an AI language model and does not have live access to the given website.

- That it only knows things recorded up until September 2021, which is the cut-off date for the data it was fed.

Thus, the tool stated that it could not determine if a site was reputable based on its data. However, the sixth site with conflicting results between our database categorization and ChatGPTs categorization was a large site named Dissident Voice. The majority of our researchers marked this site as “disinformation”, however, ChatGPT disagreed with our judgment, declaring it “generally considered a reputable source of independent and alternative news and commentary.” These small results show that while ChatGPT usually agrees with human judgment, a third-party human may still be needed to mediate between AI and human judgment. Further testing should be done on a larger dataset that was collected to study disinformation from a content standpoint.

Discussion

Our small sample results demonstrate that large-scale language models should be implemented sparingly in tasks that require classifying websites as reputable or not reputable. ChatGPT was not designed to be a disinformation analysis tool and its training data therefore has three main drawbacks for such use:

First and most importantly, ChatGPT’s responses do not account for the website’s content when providing a label. Instead, it relies upon secondary sources written by humans from its training data to classify a site.

Secondly, its training data carries a limitation and bias. ChatGPT was primarily trained upon an English data corpus collected from the internet before September 2021. Disinformation is a dynamic phenomenon deeply engaged with current societal fears. Effective disinformation campaigns generally take advantage of developing or time-sensitive topics. Thus, ChatGPT lacks the up-to-date data required for identifying and classifying disinformation sites beyond pre-written human analyses.

Finally, the training data was largely in English and caused a bias toward the English language. Foreign language website information is likely to be less informative and more likely to over-represent the views of English speakers reporting on the website.

Limitations such as these can reduce the agency of a website as well as skew the website’s classification. Our research found that ChatGPT had issues reaching data from websites that were categorized as small neutral sources or were in a language other than English.

Future Research and Conclusions

There is a lot of potential for future research in the field of generative AI, especially with ChatGPT. ChatGPT has given the general population, including both disinformation actors and UT Austin student researchers, access to AI and its capabilities. This opens a new door for more researchers to study ethical AI usages and training data, determine disinformation without human bias and query large research fields succinctly without prior knowledge. The tool can be dangerous, fast, and oh-so-tempting for all curious humans looking for guidance or for fun.

Based on our experimental results, ChatGPT cannot be used as an “arbiter of truth” in detecting disinformation websites. In the tool’s current state, it is still limited by its old and majority-English training dataset. The tool is still biased by humans as the dataset includes human analysis and write ups. In theory, the dataset could be used as an additional coder if we only cared about English sites that were available before 2021. However, its generative analysis would just repeat pre-established human sources of unknown origin instead of detecting content signals and offering new insight without bias.

Research into ethical training data and model-making for disinformation signal detection could greatly help users navigate the new infodemic. A generative AI tool built for disinformation detection would be expensive due to the large language expansion, constant updates, and adjustment to adversarial cat-and-mouse disinformation signaling mentioned above. However, the benefits of having a platform that could be trusted by users as an unbiased third party able to discern information validity after pulling from numerous sources could be incredibly useful for governments and individuals alike.

In essence? ChatGPT is not a savior but rather a new and young friend who still needs focused training in the fight against disinformation.