This blog is the first publication of the Cyber Pacific project at the Global Disinformation Lab. The goal of the project is to investigate today’s cyberspace through the lens of US strategic interest and identify a policy framework that can facilitate more effective defensive cyber operations with allies and partners in east Asia.

The Cyber domain is in its ‘messy infancy’.[1] Every day, dozens of public and private organizations wage thousands of battles for control over the flow of information that enables most modern business, warfare, and everyday life. At the same time, the terrain on which these battles are fought is continually evolving. New hardware, software, and laws continually add complexity to the already tangled web of cyberspace.

Compounding this confusion and struggle is the unsettled debate on the basic nature of ‘cyberspace’ itself. Is it a proper military domain?[2] Or is it just an ‘enabler’ of the established domains?[3] Is it actually space-like, as the name implies?[4] How should militaries operate within it?[5] What laws govern it?[6] Due to the complexity and genuine “oddness” of cyberspace, questions like these continue to defy those tasked with answering them.[7] Nevertheless, the struggle continues.

To begin this project, we decided to ‘read the room’ of the east Asian cyber domain to identify key actors and their recent activities. Given the goal of the project, we attempted to locate activity and actors within a strictly military cyber domain. However, it quickly became clear that a neatly delineated military cyber domain does not exist. While one does appear to be emerging,[8] the character of recent cyber conflict has generated a cyber organizational environment with fuzzy borders. On the one hand, this is seen in the fusion of traditional intelligence activities with military cyber operations at the highest level.[9] On the other hand, private cybersecurity and cybercrime writ large—especially in critical infrastructure—also share a porous border with the military and intelligence sides of the cyber domain. Often today’s private cybersecurity outfits pursue what can be seen as military goals, and military organizations pursue missions that were previously thought of as lying within the civilian domain.[10] As a result, we opted to ignore civilian-military distinctions in our initial survey of major actors.

What follows is postcard analysis of some of the key agencies in our target countries: the Chinese People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) Strategic Support Force (SSF), Taiwan’s Ministry of Digital Affairs (MoDA), Japan’s new Cyber Defense Command, and the United States’ Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Agency (CISA). Dozens more of similar agencies exist in various countries, but these stood out as key players. Student researchers were asked to identify key facts about the organizations (history, mission, budget, personnel, etc.), key threats to each organization, and the direction of current lines of effort in the organizations. This process of formulating this analysis has helped us clarify our image of the domain, as well as identify next steps for our research which are outlined in the conclusion.

The PLA’s Strategic Support Force – Henderson Chandler and Dylan Castro

In 2015, the PLA undertook a fundamental reorganization. The goal was to increase joint operations capabilities and prioritize maritime and information warfighting skills for its military force. Regarding informatization capabilities, the key organization to result from the shakeup was the Strategic Support Force (SSF).

Officially launched in 2015, the SSF is the 5th service branch of the PLA. It oversees operations in space, cyber, and electronic warfare domains. The SSF is organized specifically for joint operations, in line with the PLA operational concept of information operations. These aim to debilitate the enemy’s command, control, communications, computers, and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C4ISR) systems while providing the PLA with critical mission information.[11] The SSF also seeks to enhance peacetime-wartime integration of its information warfare assets, allowing the PLA to shape the operating environment to its advantage before the outbreak of conflict and transition quickly once conventional operations are underway.[12]

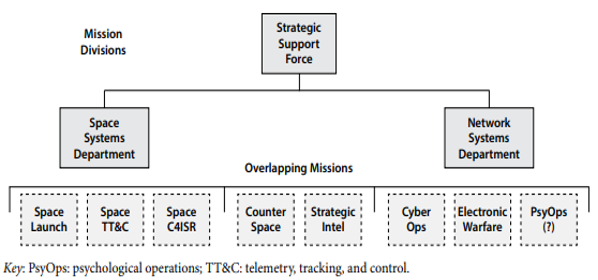

The organizational structure reflects the mission of the SSF, as seen in the split between the Space Systems Department and the Network Systems Department.[13] Together, these two groups centralize the PLA’s once scattered information warfare assets and enable their objective of “seizing and maintaining battlefield information control in contemporary information warfare”.[14] It is estimated that the SSF operates with a personnel count of 175,000.[15]

While the PLA has identified the importance of the cyber domain, their current focus within the SSF appears to be development of the Space Systems Department (SSD). [16] In the same white paper describing the necessity for the SSF, the PLA formally declared space as a warfighting domain.[17] The PLA’s recognition of space as a domain separate from cyber operations and electronic warfare is also significant and signals where the PLA is focusing for future development. Chinese military analysts see space as “the ultimate high ground” and the medium through which the PLA will deny its adversaries’ C4ISR capabilities.[18] Furthermore, the PLA’s preeminent military think tank asserts that victory on the battlefield is decided by an actor’s complementary military capabilities in space. [19]

The PLA sees the US dominance in space as a major threat and aims to close the technological gap as fast as possible.[20] In a 2016 white paper on space, the PRC committed “to build China into a space power in all respects.” China’s subsequent 2021 space white paper identified key growth areas as their civil, military, and intelligence space capabilities, indicating that the CCP and its SSF have no intentions of slowing down anytime soon. [21]

Taiwan’s Ministry of Digital Affairs – Lulia Pan and Matthew Willis

The evolution of Taiwan’s cybersecurity administration began with the National Information & Communication Security Taskforce (NICST) in 2001 and the Cyber Security Office under the Executive Yuan, Taiwan’s executive branch. Subsequently, this organization became a special unit called the Department of Cybersecurity in August 2016. In September 2022, the Department of Cybersecurity developed into the Administration of Cybersecurity – a subordinate agency under the new Ministry of Digital Affairs (MoDA).[22] In the 2023 budget proposal, MoDA was given $6.3 billion, with $30 million of that to the Administration for Cybersecurity to fund 120 personnel.

Compared to countries where this type of agency might act in isolation, MoDA has close cooperation with the private sector and even smaller white-hat hackers. Such tight-knit collaboration is a direct result of the threat faced from China. Since the island has limited resources and means to defend itself, the bureaucratic establishment has fostered a tightly interlinked, cooperative environment between public and private actors.[23]

The Chinese cyber threat looms over Taiwan and influences the development of its cyber institutions as well as its capabilities. The specific threats Taiwan faces from the PRC include, but are not limited to: data fraud, identity theft, large-scale cyber-attacks, political disinformation to affect elections as well as voting patterns, and the breakdown of critical infrastructure via cyber means.[24] The threat to infrastructure is particularly acute, as 90% of the Industrial Control System – a series of machines responsible for steering critical security frameworks – is susceptible to attacks. The severity and constancy of the Chinese cyber threat is exemplified by the millions of cyber-attacks faced by Taiwan, the majority of which are thought to originate in the PRC.[25]

Importantly, Taiwan is in a legally ambiguous position, and this affects its cooperation with other countries on cybersecurity-related topics. First, its status under international law regarding sovereignty puts it in a difficult situation for international cooperation. Only a few states recognize it (Belize, Guatemala, Haiti, Vatican City, Honduras, Marshall Islands, Nauru, Palau, Paraguay, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Tuvalu), and none maintain formal relations with both the PRC and Taiwan.[26] This contested international position and lack of official recognition has limited its participation in multilateral initiatives. For example, due to China blocking Taiwan’s efforts to join, it has not been able to join the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) – a UN specialized agency dealing with information and communication technologies (ICT). Membership in this organization allows a country to participate in setting standards around ICTs, including aeronautical and maritime navigation, next-generation networks (such as 5G), and artificial intelligence.[27] Considering Taiwanese society’s high degree of digitalization, participating in this dialogue would be beneficial. It is true Taiwan has engaged with other countries over such cyber-related issues with more informal avenues such as the Taiwan International Governance Forum (TWIGF), but participation and collaboration remain relatively limited.[28]

Taiwan is a highly digitized and technologically advanced society with wide usage of online communication, digital information sharing, and online and digital payments. This means that cybercrime is widely present throughout the country, where cyber-enabled human trafficking, fraud, theft, and illegal pornography are common. This has caused the MoDA in recent years to redouble its efforts in addressing cyber-crime and potential further penetration from smaller foreign actors.[29]

Japan Self-defense Forces Cyber Defense Command – Kem Hosoya

The newly formed Japan Self-defense Forces (JSDF) Cyber Defense Command is the primary organization tasked with defending the Japanese military network against cyberattacks.[30] It is a joint operations unit created to centralize the efforts of the separate service branch cyber operations units. It was previously known as the Cyber Defense Unit, which operated under the C4 Systems command starting in 2008, with a reorganization in 2014. Currently, it operates with 540 members and a budget of ¥34.2 billion (roughly thirty million USD).[31]

The Cyber Defense Command has a ‘six pillar structure’ for its cybersecurity defense goals.

- Security system management, maintaining internet safety within the military

- Cyber attack defense, defending the JSDF against cyberattacks; each service branch also has their own individual cyber attack defense team

- System equipment management, maintaining hardware used within the JSDF Cyber Defense Command

- Research, developing new cyber defense strategies

- Human resource development, training recruits

- Diplomacy, handling all global diplomatic ties[32]

The Cyber Defense Command’s biggest problem is its relative underdevelopment and susceptibility to breaches. The average number of malware breaches per attempt on Japanese networks is 98.6%, indicating a nearly 100% success rate.[33] The number of attacks is also at a high level, indicating that the current defense system is not deterring attackers. The relatively small staff and budget the Cyber Defense Command currently possesses makes tackling these problems difficult.

Furthermore, Japan’s legal system and social norms make attempts to improve cyber-defense difficult by prohibiting an ‘active defense’ approach. Due to Article 9 of Japan’s constitution, while the military is allowed to defend itself if attacked, it cannot retaliate against any attacks, nor can it conduct preventative offensive measures. As the legal system and social norms are difficult to change, the Cyber Defense Command has strengthened its human resource development program and ties with other militaries such as the United States, NATO, and the UK to participate in joint collaborations that target global cybersecurity issues.

While the newly strengthened Prime Minister’s office (kantei) continues to consolidate and modernize defensive military and intelligence capacities, the Japanese government faces an uphill battle to reinforce its efforts with significantly increased levels of investment. This is primarily due to the currently weak state of Japanese economic growth, constitutional constraints on military activity, and the prevailing pacifist preference of the Japanese people.

The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Agency – Francisco Costa Nunes and Joe Eduard Rucker

The Department of Homeland Security formed the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Agency (CISA) on November 16th, 2018 to succeed and elevate the efforts of the National Protection and Programs Directorate (NPPD). NPPD focused on reducing and eliminating threats to US physical and cyber infrastructure. CISA’s mission is to understand, analyze, and manage cyber and physical risks to the US’s critical infrastructure. As of 2022, CISA has a budget of approximately two billion USD and employs over 2,400 civilians.[34]

CISA has identified four primary goals:

1. Cyber Defense: To ensure the defense and resilience of cyberspace

2. Risk Reduction and Resilience: To reduce the risks and strengthen the resilience of the US’s critical infrastructure

3. Operational Collaboration: To strengthen the nation’s operational collaboration and information sharing

4. Agency Unification: To unify CISA through integrated functions, capabilities, and workforces

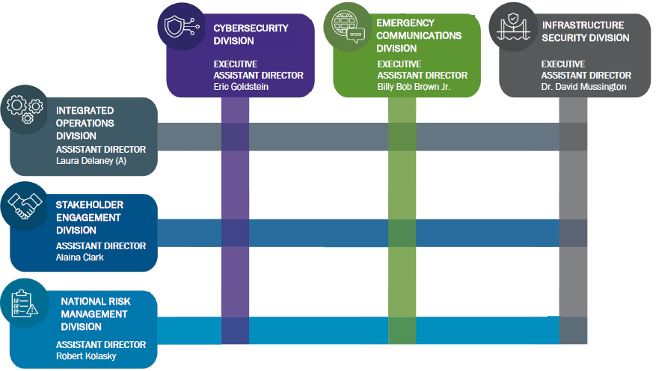

To achieve these goals, CISA has three primary operational divisions; the Cybersecurity Division (CSD), the Infrastructure Security Division (ISD), and the Emergency Communications Division (ECD). CSD attempts to detect, analyze, mitigate, and respond to significant cyber threats. ISD works to enhance the security and resiliency of the US’s critical infrastructures. Finally, ECD provides training, coordination, tools, guidance, and public standards to help partners develop their emergency communications capabilities.

CISA also has three horizontally integrated delivery and coordination divisions: the National Risk Management Center (NRMC), the Integrated Operations Division (IOD), and the Stakeholder Engagement Division (SED). NRMC works with partners to analyze and reduce risks that impact national critical functions by creating and executing management plans. IOD coordinates with partners and stakeholders throughout the US to deliver CISA services. Lastly, SED facilitates and manages stakeholder engagements and partnerships to reduce national security risks.

In addition to these divisions, CISA houses several groups that facilitate public and private sector communication and collaboration, mandated by the National Infrastructure Protection Program (NIPP) of 2013. The “Sector Coordinating Councils” (SCCs) are self-organized and self-governed councils representing the private sector’s voice to guide policies surrounding the resilience and security of critical infrastructures. The “Government Coordinating Councils” (GCCs) are the public sector’s counterpart to the SCCs, facilitating interagency communication. The SCCs and GCCs work together to plan, implement, and execute the protection of critical infrastructures nationwide.

CISA also leads a public-private partnership line of effort. This is headed by the Joint Cyber Defense Collaborative (JCDC), which partners with public and private sector entities to drive collective action and create a unified cyber defense front within the United States. The JCDC currently has twenty-one private sector partners, which include Microsoft, AT&T, and Cisco. The eight public partners include CISA, the Office of the National Cyber Director, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI), the FBI, the NSA, the US Secret Service, the Department of Defense (DoD), and the Department of Justice (DoJ). Furthermore, CISA recently formed the Cyber Safety Review Board (CSRB), which brings together government and industry leaders to review and assess significant cyber events that impact the public and private sectors. Lastly, in this line of effort CISA launched the Cyber Innovation Fellows Initiative, which offers private sector workers the opportunity to work within the agency temporarily.

CISA’s key threats are cyber attacks (e.g., ransomware, DDoS attacks, wiper attacks) initiated by foreign national governments, terrorist organizations, and hacker groups. Each actor employs different tactics to accomplish unique goals. For example, one important foreign actor is Chinese state-sponsored hacker groups (e.g., APT40, Leviathan, Hellsing). These groups use cyber espionage, targeting public and private sector entities, to increase China’s power in all domains. Within the public sector, on the other hand, hackers use malware to disrupt government website operations and steal sensitive information. Non-state-sponsored hacker groups also pose a significant threat. In 2021, the Russian hacker group known as DarkSide conducted a ransomware attack on the Colonial Pipeline company, resulting in the largest pipeline shutdown in American history. In the end, the company decided to pay the $4.4 million ransom requested by the hackers.[35]

CISA responds to these threats using threat prevention and cybersecurity response. The Enhanced Cybersecurity Services (ECS) program provides intrusion detection and prevention services to partners. Alongside this, they provide information sharing across the public and private sectors through the National Cyber Awareness System. The Hunt and Incident Response Team (HIRT), meanwhile, manages and coordinates actions to resolve cyber threat incidents before and after they arise.

In the present day, cyber threats are everywhere and affect everyone. Cyber and physical infrastructure are increasingly merging and are more reliant on each other. The failure of one critical infrastructure sector now has a cascading effect on all, which poses a grave US national security threat. CISA is working towards developing and strengthening a unified cyber defense front — combining both the public and private sectors — to protect all American critical infrastructure.

Lessons Learned and Next Steps

In surveying the main actors of the east Asian cyber domain a few things became clear. Firstly, the cyber domain has a boundary problem. Its fuzzy borders have led to jumbled jurisdictions, responsibilities, and priorities. Moreover, nearly everyone is in the domain, from non-state to state actors, and the means and vectors for cyber attacks are proliferating. It is therefore difficult to comprehensively map the terrain of the current cyber domain; it is simply overwhelming. Any subsequent cartographic efforts should therefore be as mission-specific as possible.

Secondly, organizational evolution in the cyber domain is occurring at different speeds. To take a national-military example, CYBERCOM was stood up in 2009, the PLA’s SSF in 2015, Taiwan’s Information, Communication, and Electronic Warfare Command in 2017, and Japan’s Cyber Defense Command in 2022. These different speeds are the results of the different legal and political environments in which the organizations are fostered. Further study is needed to clarify these environments and their effects on cyber domain adaptation.[36]

Overall, the boundary and evolution problems combine to create an organizational landscape that is messy and in constant motion. In trying to make sense of how the current cyber-focused organizations fit together we were mostly left scratching our heads.

In light of these findings, our next step is to approach the research question from the narrower lens of national cyber strategies and policies. How are states in east Asia wielding their economic and political power to shape the cyber domain, and towards what ends? How do they mobilize their military forces in these strategies and policies, and what unique operational constructs to they employ to do so? Who seems to be wielding cyber power most effectively, and what can the US and allies learn from this?

Stay tuned!

-Kevin Lentz

[1] Wilner, in “US Cyber Deterrence” uses this phrase to describe the deterrence debate. It seems just as apt as a description of the domain overall.

[2] https://warontherocks.com/2021/05/why-the-united-states-needs-an-independent-cyber-force/

[3] Kallberg, “Strategic Cyberwar Theory – A Foundation for Designing Decisive Strategic Cyber Operations.”

[4] Miller, “THE SPACE BETWEEN: POLICY IMPLICATIONS FOR THE CONCEPTUALIZATION OF CYBERSPACE AS A DOMAIN.”

[5] Crowther, “The Cyber Domain.”

[6] E.g. https://thestrategybridge.org/the-bridge/2021/7/8/cyberspace-is-an-analogy-not-a-domain-rethinking-domains-and-layers-of-warfare-for-the-information-age, Crowther, Glenn Alexander. “The Cyber Domain.” The Cyber Defense Review 2, no. 3 (2017): 63–78. Ormrod, David, and Benjamin Turnbull. “The Cyber Conceptual Framework for Developing Military Doctrine.” Defence Studies 16, no. 3 (July 2, 2016): 270–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/14702436.2016.1187568.

[7] Singer and Cole, “Cyber Solarium Report,” 28.

[8] https://www.cyberscoop.com/biden-nspm-13-pentagon-cyber-operations/

[9] neatly exemplified by the current ‘dual hat’ command of the United States’ National Security Agency (NSA) and Cyber Command (CYBERCOM)

[10] The former is well exemplified by Microsoft’s war time support of Ukraine: https://blogs.microsoft.com/on-the-issues/2022/06/22/defending-ukraine-early-lessons-from-the-cyber-war/

[11] Kitchen, “Informatized Wars.”

[12] Costello and McReynolds, China’s Strategic Support Force: A Force for a New Era, 12.

[13] It is unknown exactly how resources are split between the two departments.

[14] Cordesman, “Chinese Strategy and Military Forces in 2021,”120.

[15] The International Institute for Strategic Studies, “The Military Balance 2021,” 255.

[16] Cyber operations fall under the Network Systems Department. Costello and McReynolds, “CHINA STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 13,” 7.

[17] Office of the Secretary of Defense, “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,” 65.

[18] Pollpeter, Chase, and Heginbotham, “The Creation of the PLA Strategic Support Force and Its Implications for Chinese Military Space Operations,” 7.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Todd Harrison et al.,”Space Threat Assessment 2022,”8.

[22] Robbins, Sam, Chia-Shuo Tang, and The Diplomat. 2022. “Hopes And Concerns For Taiwan’S New Ministry Of Digital Affairs”. Thediplomat.Com. https://thediplomat.com/2022/08/hopes-and-concerns-for-taiwans-new-ministry-of-digital-affairs/.

[23] Romaniuk, Scott, and Mary Manjikian. Routledge Companion to Global Cyber-Security Strategy, 2020. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429399718.

[24] Pryor, Crystal D., Tania Garcia-Millan, Jeffrey Gelman, Tanvi Madan, Scott Moore, Crystal Pryor, Lisa Reijula, et al. “Taiwan’s Cybersecurity Landscape and Opportunities for Regional Partnership.” Perspectives on Taiwan. Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), 2019. https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep22549.5.

[25] Shan, Shelley. “Record Number of Cyberattacks Reported – Taipei Times.” Accessed November 18, 2022. https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2022/08/05/2003783012.

[26] Myers, Steven Lee. “Taiwan Loses Nicaragua as Ally as Tensions With China Rise.” The New York Times, December 10, 2021, sec. World. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/10/world/asia/taiwan-nicaragua-china.html.

[27] Cordell, Kristen, “The International Telecommunication Union: The Most Important UN Agency You Have Never Heard Of”. 2022. Csis.Org. https://www.csis.org/analysis/international-telecommunication-union-most-important-un-agency-you-have-never-heard.

[28] Romaniuk, Scott, and Mary Manjikian. Routledge Companion to Global Cyber-Security Strategy, 2020. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429399718.

[29] Romaniuk, Scott, and Mary Manjikian. Routledge Companion to Global Cyber-Security Strategy, 2020. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429399718.

[30] Defense of Japan 2022

[31] “日本の防衛省の予算2022年.” P. 6 This does not account for purchasing power parity, and is distorted by the current unusual exchange rate. IISS. “Cyber Power – Tier Three.” Accessed October 14, 2022. https://www.iiss.org/blogs/research-paper/2021/06/cyber-power—tier-three.

[32] “我が国の防衛と予算-令和5年度概算要求の概要- .” 我が国の防衛と予算. 防衛省・自衛隊, August 31, 2022. https://www.mod.go.jp/j/yosan/yosan_gaiyo/2023/yosan_20220831.pdf.

[33] Katagiri, Nori. “From Cyber Denial to Cyber Punishment: What Keeps Japanese Warriors from Active Defense Operations?” Asian Security 17, no. 3 (September 2, 2021): 332. https://doi.org/10.1080/14799855.2021.1896495.

[34] “FY 2022 Budget-in-Brief | Homeland Security.” Accessed October 31, 2022. https://www.dhs.gov/publication/fy-2022-budget-brief.

[35] William Turton and Kartikay Mehrotra, “Colonial Pipeline Cyber Attack: Hackers Used Compromised Password,” Bloomberg.com (Bloomberg, June 4, 2021), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-06-04/hackers-breached-colonial-pipeline-using-compromised-password

[36] Max Smeets has recently made a substantial contribution to this line of enquiry, “No Shortcuts; Why States Struggle to Develop a Military Cyber Force.” Chs. 2 & 3