By Connor Cowman, Aaron Hernandez, Jujhar Singh

The University of Texas at Austin – Global Disinformation Lab

Faculty Lead – Kim Nguyen

June 7, 2023

Key Takeaways:

- The FSB and the GRU are the two main disinformation actors within the Russian government. They are deeply connected with cyber networks and foreign influence actors, such as the Internet Research Agency (IRA), that are responsible for the creation and distribution of mis- and disinformation materials aiming to influence American elections.

- The Kremlin seeks to push Russian propaganda into the information mainstream and to foment discontent among the American constituency on both the right- and left-wings of the political spectrum.

- Russian disinformation has been most successful in sowing discord in the context of American elections, due to the effectiveness of organizations such as the IRA. However, with a growing understanding of Russian influence operations, and subsequent measures to counter their impact, Russia is gaining less traction in the West from their information campaigns involving the Russia-Ukraine War.

- Chinese disinformation operations have traditionally had little impact within the United States. However, as the efficacy of the United Front Work Department increases and the PRC expands its influence operations on online media platforms targeting the West, Chinese disinformation has the potential to increase in effectiveness among vulnerable American populations such as far-left groups and the Chinese diaspora.

- The Russian and Chinese domestic information environments are increasingly melding with one another, leading to cooperation in the disinformation space – particularly in the context of the Russia-Ukraine War. This cooperation has the potential to generate effective tactics and angles that might be used to influence American voters in future elections.

Russian and Chinese disinformation campaigns are the most threatening to the integrity of American elections. Understanding their disinformation infrastructure and operations in the information space can inform and empower Americans to recognize disinformation before they vote and help policymakers increase the resiliency of their constituencies.

Russian Influence Operation Architecture

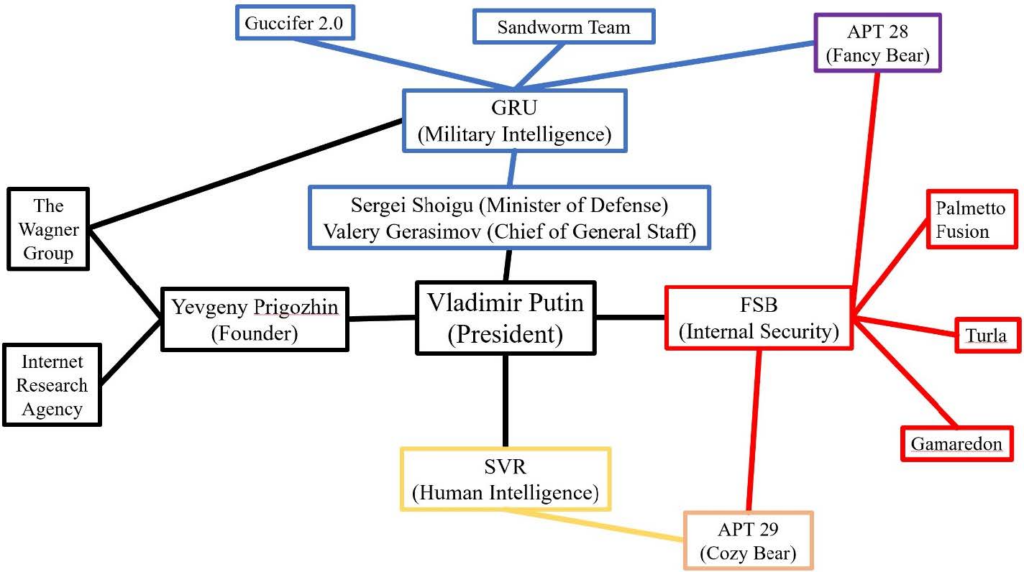

According to the National Intelligence Council’s assessment of foreign threats to the 2020 presidential election, the most impactful actor in the foreign adversary disinformation space is the Russian Federation.[1] There are three agencies in the Russian government which are connected to foreign influence operations: the Federal Security Service (FSB), the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), and Main Directorate of the General Staff of the Armed Forces (GU), more commonly known by its Soviet-era name, the Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU).[2] The FSB, while traditionally responsible solely for counterintelligence and surveillance operations within Russia, now has considerable impact on Russia’s foreign influence operations due to its connections to multiple disinformation networks. The FSB and the GRU, Russia’s military intelligence body, are the most active players in cyberspace, while the SVR mainly focuses on human intelligence with a relatively minor impact in cyber affairs.

Each of these agencies is affiliated with one or more Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs), the cyber networks which create and coordinate influence and interference operations. There appear to be seven major networks that are the primary influence organizations in Russia’s mis- and disinformation campaigns. Figure 1 illustrates the major cyber networks and their connections to the Russian intelligence services. There are also six minor APTs whose governmental links are unclear.

APTs 28 and 29 are two of the most prolific APTs in Western election interference. These groups carried out the 2016 phishing attacks on the Democratic National Committee which sought to denigrate former Secretary Hillary Clinton and create distrust within the public regarding American election security.[3] Additionally, APT 28 was responsible for cyber-attacks against the German parliament in 2015 and 2016 and against the campaign of French President Emmanuel Macron in 2017. They sought to steal sensitive information that could have been used to influence both countries’ elections.[4] As evidenced by their track record, these APTs are seasoned in the art of election interference; however, cybersecurity defenses have reduced these actors’ advancements.

Figure 1 – Major Foreign Influence Networks Associated with Russian Intelligence Services [5]

The GRU is arguably Russia’s most powerful information operation actor because of its large amounts of resources and connection to the Internet Research Agency (IRA).[6] The IRA is a Russian company founded in 2013 by oligarch Yevgeny Prigozhin that engages in massive disinformation operations. The IRA generated content which was exposed to more than 126 million Americans in the lead up to the 2016 election.[7] Prigozhin recently boasted before the 2022 U.S. midterm elections that his organization “interfered [in U.S. elections]…are interfering and…will continue to interfere.”[8] While the Russian government does not acknowledge links between the IRA and GRU, Prigozhin’s connection to both actors via the Wagner Group implies some complicity between the Russian state and private Russian companies. The Wagner Group is closely connected to the GRU and other Russian state cyber actors and serves as the nexus point for GRU-IRA cooperation in areas such as email thefts and election interference, as seen in Figure 1.[9]

In summary, the FSB and the GRU are the two main disinformation actors within the Russian government, with minor influence from the SVR. Despite the SVR’s likely minimal influence, Sergey Naryshkin, the organization’s head, is a longtime acquaintance of Putin, potentially giving the SVR outsized influence regarding certain decisions. The GRU’s connection with the IRA is particularly notable given this organization’s infamy and connection to Wagner Group founder, Yevgeny Prigozhin. Each agency has deep connections with various influence actors which are responsible for the creation and distribution of mis- and disinformation materials aiming to influence American elections. Additionally, certain APTs, such as APT 28, execute hacking operations to acquire sensitive materials for the same purpose.

Russian Foreign Influence Campaigns

Since at least the 2000s, Russia has sought to create discord in Western publics, particularly in the U.S., by employing remnants of the Soviet KGB system to conduct information operations.[10] A key component of the KGB’s dezinformatsiia strategy involved sowing mistrust in the political system. For example, using the propaganda news outlet RT, formerly known as Russia Today, the Kremlin sought to spread conspiracy theories about 9/11 to further skew existing skepticism surrounding the event towards the idea that the U.S. government played a deceitful or even malicious role in the origins and handling of 9/11.[11] More recently, Russian disinformation actors have used a “firehose of falsehoods” targeting both left- and right-wing audiences in the U.S. and other Western countries to spread disinformation about the efficacy behind COVID-19 prevention measures and vaccines taken by state governments and the intentions these governments might have in promoting these strategies.[12]When considering the threat of Russian disinformation with respect to influencing American public opinion or U.S. elections, it is necessary to keep in mind the goals of these actors: 1) to push Russian propaganda into the information mainstream and 2) to spread chaos and build discontent among the American constituency.

Russian Propaganda Enters the American Right-Wing and Left-Wing Information Mainstream

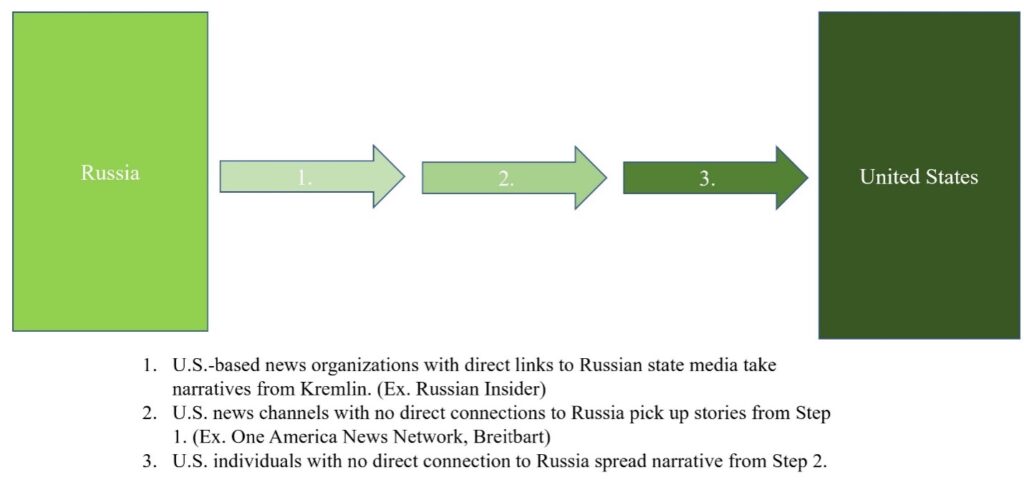

In their aims to sow discord and build tensions in the U.S., the Kremlin efforts to influence American audiences include both the right- and left-wings of the political spectrum. Pushing Russian narratives into the American right-wing information landscape is generally accomplished through a multi-step messaging process, as seen in Figure 2.

Right-wing pundits who have no direct connection to Russia can help the Kremlin influence American elections merely by amplifying Russian-developed conspiracies. For example, by echoing the Russian conspiracy that the U.S. funded bioweapons in Ukraine, these pundits are redirecting the focus on the war in Ukraine to a rhetoric that questions the West’s moral authority and that is sympathetic to the Russian government.[13] These conspiracies, combined with a growing sense of isolationism among far-right supporters and the pandemic-induced economic stresses, create a sentiment weary of U.S. material support to Ukraine. Talking points such as “Why are we sending money to Ukraine when there is inflation in the U.S.?” target and manipulate American economic anxieties and have been inserted into conversations surrounding the debt ceiling in the U.S. Congress.

Figure 2 – How Russian Narratives Enter the American Right-Wing Information Mainstream

For left-wing media, the spread of Russian messaging relies on the use of individual “content creators” or “independent journalists” as opposed to the unified clear line of rhetoric as seen from the right. These actors may receive financial compensation from the few outlets that offer it, such as RT America, a Russian English-language news channel which brings the Russian perspective on global news. Historically, Russian disinformation operations targeted the left-wing during the Occupy Wall Street movement in 2011.[14] However, that has since transitioned to target a broader left-wing audience that often feels disenfranchised from politics. The Pew Research Center reports that the “outsider left,” those described as “young, liberal, and discontented Democrats…were 9 percentage points less likely to vote in the 2020 presidential election than the average adult citizen and 11 points less likely to vote than the average Democrat or Democratic-leaning citizen.”[15]

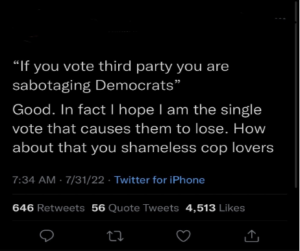

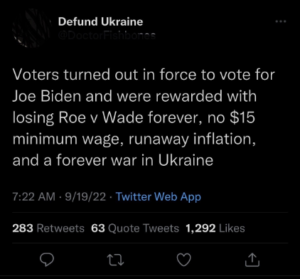

The targeted messaging from Kremlin-supported pages was to not participate in the two-party system. The online left-wing movement #BernieOrBust is representative of this phenomenon.[16] This campaign sought to include Senator Bernie Sanders in the general election, splitting the vote as a third-party candidate, or to worsen voter inactivity in the general presidential election based on discontent with the primary results.[17] Additionally, this message was strengthened because of the feeling of discontent from the “outsider left” with the proposed Democratic candidates. The “outsider left” is one part of “an overwhelming majority (86%)” of voters who “say that they usually feel like none of the candidates for public office represent their views well.”[18] This narrative has extended past the 2020 elections into the present, and it has the potential to be bolstered by those aggrieved with the current political system. Furthermore, even the Sanders campaign recognized the possibility of this message stemming from Russian troll farms.[19] The Twitter posts in Figures 3 and 4, both published in 2022, are representative of this concept, as they demonstrate a sense of dissatisfaction with the establishment wing of the Democratic Party. These individuals can thus use this as an avenue to peddle Kremlin supported messaging.[20] Furthermore, this rhetoric shows that the “outsider left” often publicly tests Democratic politicians of their adherence to progressive values, causing tension and distrust between them and their voter bases.

Figure 3 – Twitter post illustrating the “outsider left” dissatisfied with the Democratic Party establishment.

Figure 4 – A second Twitter post illustrating the “outsider left” discontent with the Democratic Party establishment.

The Twitter post in Figure 5 comes from a far-left “independent journalist” who has made a reputation providing content about the Russia-Ukraine War from the Russian perspective and has also appeared on RT America as a contributor for numerous video segments. His Twitter post in Figure 5 references the 2020 election and exemplifies the disgruntled left’s view of President Biden, the Democratic establishment’s choice for the office.

Figure 5 – Twitter post from a far-left journalist reflecting a common sentiment among the “outsider left” about refusing to vote in the 2020 presidential election. *The journalist’s name has been removed from the post.

The widespread involvement of Kremlin-connected operatives in the realm of foreign influence operations is well-documented, including the IRA’s notorious involvement and aggressive campaign to shape U.S. elections.

The Internet Research Agency and Its Influence in American Elections

One of the most significant steps in increasing the disinformation volume and creating a disinformation apparatus modeled on the KGB came in 2013 with the establishment of the IRA. This organization became infamous for its broadscale information operations in which 126 million Americans were exposed to its content before the 2016 presidential election.[21] Possible links have also been identified between the IRA and troll farms in Kosovo and North Macedonia which ran 19 of the 20 most popular Christian Facebook pages in the run-up to the 2020 U.S. election and whose content reached 140 million Americans.[22] While posting traditional content expected from Christian Facebook pages, these troll farms also subtly included socially divisive messaging such as memes comparing former Secretary Hillary Clinton to Satan.[23] Beyond Christian social media pages, the troll farms also created fake rallies for primarily pro-Trump audiences and formed a group dedicated to the South rising again that garnered over 130,000 likes.[24] The IRA is now under U.S. indictment for its role in disinformation operations during the 2016 and 2018 elections. However, it still appears to be involved in certain Russian disinformation operations. In August 2022, Meta shut down a troll network on its platforms with close connections to the IRA and Yevgeny Prigozhin.[25] As Russian influence tactics become better studied and understood, Western audiences find themselves better equipped to counter Russian operations, reducing the effectiveness of the Kremlin’s messaging, especially as it pertains to the Russia-Ukraine War.

(In)Effectiveness of Russian Disinformation Campaigns on the Russia-Ukraine War

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the IRA and Russian security services have focused on legitimizing the “special military operation” and dividing Western audiences. To shape the narrative on the “special military operation,” the IRA and similar groups used reflexive control tactics that were also used during the 2014 Euromaidan revolution in Ukraine and the subsequent invasion of Crimea.[26] However, it appears that the disinformation campaign focused on the war in Ukraine is not gaining the traction in the West that the previous operations garnered, due in large part to the Ukrainian “information counteroffensive.”[27] The counteroffensive tactics include video showing the devastation inflicted upon Ukraine and the Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s frankness and camera presence, which have been contrasted with Putin’s less charismatic delivery of information.[28]

Regardless, Russia is not giving up on their disinformation apparatus – there was a 433% increase in funding granted to government spending on “mass media” between February and March 2022.[29] Russian disinformation networks continue to subvert bans on their own accounts and those of Russian state media through the sheer volume and use of sleeper accounts.[30] It is also highly likely that there are disinformation operatives or networks within Europe focused on reshaping the narrative surrounding the Russia-Ukraine war in places like the European Union, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland.[31] Furthermore, it is also noteworthy that while the Kremlin is struggling to gain traction in the West, Russian disinformation has attained significant engagement with populations in the Global South.[32] The narrative that Western sanctions against Russia are the primary cause for growing food insecurity in regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa, an example of Russian propaganda advanced in the Global South, has been repeated by an African head of state.[33]

The U.S. is a large and diverse country, and while these attributes are strengths, they can also be exploited. Given that Russia’s primary objective with their disinformation operations seems to involve sowing social discord wherever possible, any groups in the U.S. with significant levels of suspicion toward official narratives and poor information literacy are likely at risk of being influenced. Despite the limited success Russia has seen in the West with its propaganda efforts in relation to the war in Ukraine, the problems of inflation, rising energy prices, and arms transfers to Ukraine present angles for Russian disinformation to target susceptible, isolationist-leaning American demographics.

Chinese Influence Operation Architecture

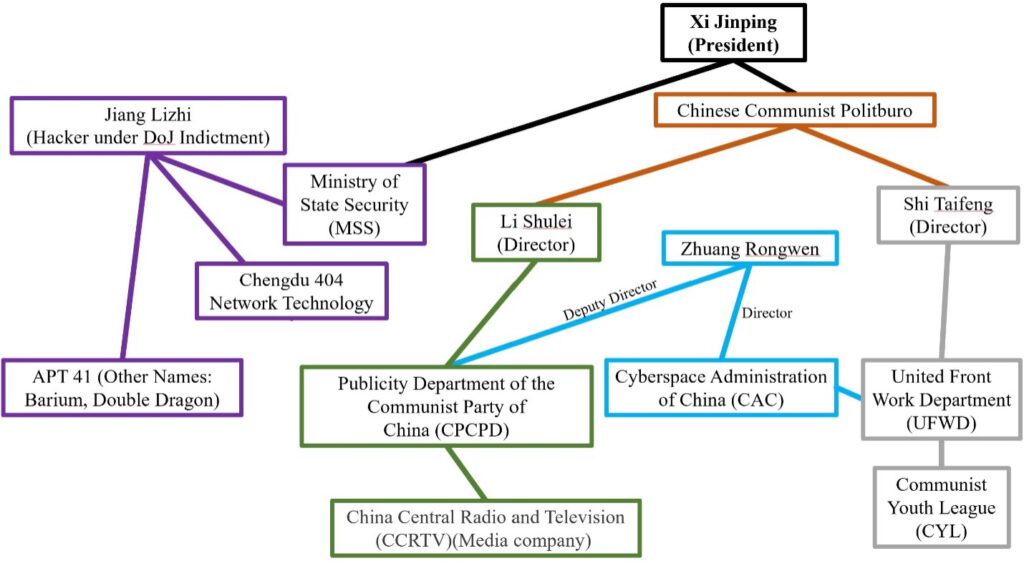

Compared to Russia’s deep networks and experience in the disinformation space, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is a relatively new player in the field. Within the CCP, there are three main bodies that have some connection to information operations inside and outside of China: 1) the Publicity Department of the Communist Party of China (CPCPD), 2) the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), and 3) the United Front Work Department (UFWD). The Publicity Department manages China’s information dissemination system and matters relating to ideology.[34] This organization also oversees publication of media within China and runs China Central Radio and Television (CCRTV), the state broadcasting service. The Cyberspace Administration primarily regulates and enforces internet content.[35] Finally, although its primary responsibilities are domestic, China’s United Front Work Department serves as the outward facing arm of the CCP responsible for coordinating influence operations by co-opting or directing overseas Chinese organizations or individuals.[36] This makes the UFWD one of the most powerful agencies within the CCP.[37] Figure 6 illustrates the main Chinese actors responsible for information and influence operations.

Figure 6 – Major Chinese Actors in Information and Influence Operations

The UFWD is also bolstered by the Communist Youth League (CYL), an organization for people between the ages of 14 and 35. Originally a network for young Chinese citizens to demonstrate ideological commitment and improve career opportunities within the CCP, it morphed into a Party recruitment tool and facilitator of UFWD projects.[38] The CYL serves as an intermediary between Chinese students abroad and the leadership within the UFWD, promotes the efficacy of UFWD work to CCP leadership, and generally collaborates with the UFWD on projects bolstering China’s image abroad and recruiting new cadres, particularly those with experience abroad.[39] Furthermore, the CYL has an increasingly significant platform on social media, making it a formidable tool in communicating CCP messaging to youth.[40]

Additionally, the shared leadership between the CPCPD and CAC, as illustrated in Figure 6, provides an uncommon nexus of coordination between agencies in the traditionally rigid CCP governing hierarchy. Each of these organizations have powerful information control mechanisms, and potential use of these tools in cooperation with the UFWD in foreign influence campaigns is not unlikely. [41] Whereas the CPCPD and CAC possess the cyber hardware to conduct digital operations, the UFWD has the ideological software to give substance to such campaigns.

One possible example of recent UFWD operations are the organization’s suspected attempts to push a pro-unification message while simultaneously supporting underground criminal activity in Taiwan.[42] The Chinese Unity Promotion Party (CUPP) in Taiwan is headed by Chang An-lo, a key member of the Bamboo Union organization crime group.[43] Former Taiwanese President Lee Teng-hui hinted at connections between Chang and the CCP in a 2017 speech when he suggested that Chinese United Front strategies seek to recruit pro-unification supporters and sponsor criminal activities.[44] Chang An-lo is still the president of CUPP today, suggesting that UFWD influence operations continue through this organization.

In summary, the UFWD, with some facilitation assistance from the CYL, likely generates the majority of the CCP’s overseas mis- and disinformation influence operations. However, the domestically focused CAC and CPCPD cannot be ignored when assessing Chinese influence missions due to their infrastructural capabilities and potential to bolster the work of the UFWD.

Chinese Foreign Influence Campaigns

In the past year, Chinese foreign disinformation has ramped up in the United States. Taiwan-based Doublethink Lab, a civil society organization dedicated to studying Chinese disinformation, rated the U.S. as having a high level (>90%) of pressure exerted against it. This means that CCP-affiliated actors use the threat of economic punishment to change the behavior of the American people.[45] In addition to using their economic power, the PRC employs other methods to shape opinion and affect outcomes favorable to the CCP, including the use of “discourse power,” encouraging the actions of “wolf warrior” diplomats, and through Western internet personalities, online news media, and social media. These influence operations can affect the American populations most vulnerable to CCP propaganda: the far-left wing of the political spectrum and the Chinese diaspora. As the PRC continues their attempts to influence Western opinion, it is important to understand how Taiwan, who encounters the highest volume of CCP disinformation, counters Chinese mis- and disinformation, and through these lessons learned, find the most effective measures to adopt in the U.S.

“Discourse Power”

As a form of soft power, the PRC uses “discourse power” to beautify the Chinese value system and ideology, particularly that which is official CCP doctrine.[46] Chinese disinformation actors aim to promote this positive and often artificial image of China to American audiences.[47] Those promoting these messages can be official members of the Chinese government or a Westerner compensated to promote pro-Chinese propaganda. This concept is important to Chinese election disinformation because it reflects the idea that for too long China was not considered an equal of Western powers and had its right of co-equal discourse stripped away from it. Now that China has become the world’s second largest economy and a geopolitical superpower, this newfound discourse power can and should, in the eyes of the CCP, be used internationally to push a Chinese agenda to correct for years of weakness, even if this means creating disinformation to do so.[48]

“Wolf Warrior” Diplomats

The CCP’s “wolf warrior” diplomats are the most notorious Chinese propaganda agents. The wolf warrior namesake derives from a Chinese film of the same name in which heroic Chinese soldiers fight off an evil ex-Navy SEAL American mercenary.[49] Wolf warriors spread all manner of disinformation and propaganda directed towards Western audiences on Twitter, the medium most conducive to text-based engagement, such as anti-American memes and mis- and disinformation about COVID-19.[50], [51], [52] While not all Chinese diplomats are wolf warriors, the ones who identify as such attract the most attention – from both foreigners and party leadership in Beijing.[53] Up until recently, successfully promoting pro-China messaging can advance wolf warriors’ personal and professional lives, as demonstrated by Zhao Lijian. Zhao was a well-known wolf warrior diplomat and a propagator of conspiracy theories, and his aggressive anti-American rhetoric appeared to have contributed to his 2019 promotion as the Deputy Director of the Chinese Foreign Ministry.[54], [55] Given the apparent career benefits associated with outward facing verbal provocations and the aforementioned political culture surrounding promotion in China, much of this information warfare seemed to be directed from the top down and deemed desirable by top party officials.[56], [57] However, in early 2023, Chinese leaders appeared to waiver on wolf warrior diplomacy, as evidenced in the CCP’s recent reassignment of Zhao Lijian to an obscure position with the Department of Boundary and Ocean Affairs.[58] It is possible that Beijing views it as a problem for the country’s global image. This suggests that China may be open to adjusting their overt messaging to account for the current geopolitical situation.

Influence Operations Through American Internet Personalities and Online News Media

The information warfare becomes dangerous and threatening to the integrity of U.S. elections when Americans begin believing the presented narratives. However, overt members of the CCP who spread disinformation likely find it difficult to influence public opinion in the U.S. due to general American skepticism of governmental attempts to influence the information environment.[59] The CCP is aware of this and employs, or otherwise co-opts, Western internet personalities, YouTubers, and journalists to push both subtle and overt political propaganda.[60]

The Grayzone News, an American online publication that describes itself as “an independent news website dedicated to original investigative journalism and analysis on politics and empire,” is potentially susceptible to Chinese influence.[61] Its website boasts of positive reactions to its journalism from a U.S. congressman and a well-known American filmmaker, likely intended to boost readership and credibility.[62] The publication frequently runs articles sympathetic to China and other authoritarian regimes such as Russia, Iran, and Venezuela.[63], [64], [65], [66] However, the platform has been particularly friendly to the Chinese regime by condemning the Hong Kong pro-democracy protests in 2019 as U.S. meddling and repeatedly denying the Uyghur genocide in Xinjiang.[67], [68] In return for this friendly treatment, The Grayzone has been amplified by the Global Times, the CCP’s outward facing propaganda newspaper.[69] Additionally, reporting from The Grayzone has received great praise from the aforementioned wolf warrior diplomat Zhao Lijian.[70] This support from a senior CCP official has likely increased readership for The Grayzone, which provides the publication with monetary incentives to continue their friendliness towards the regime in Beijing.[71]

This investment in internet-based Western actors appears to be a change in strategy from Beijing’s previous influence operations in the United States. In 2015, Reuters reported that at least 15 U.S.-based radio stations indirectly funded by the state-owned China Radio International, via now defunct front company G&E Studio, Inc., consistently broadcasted pro-CCP propaganda.[72] Arguably the most influential among these was WCRW, a station broadcasting from Loudoun, VA, which was forced to register as a foreign agent directed by the Chinese state-run China Global Television Network (CGTN).[73] However, a U.S. Department of Justice filing shows that in December 2021, WCRW ended its relationship with CGTN.[74] This announcement, which coincided with the dissolution of G&E Studio, Inc. in December 2021, suggests that the CCP is shifting away from radio-based influence operations.[75]

Influence Operations on Social Media

Although the CCP had a muted involvement in the 2020 U.S. elections, it exercised more of its capabilities in the digital space in the 2022 U.S. midterm elections. Foremost among these influence attempts was the DRAGONBRIDGE campaign. Perpetrated by the Chinese threat group APT41, this campaign sought to discourage voting through undermining confidence in the democratic system and to stoke fears of a coming civil war in the United States.[76] Additionally, Google reported in January 2023 that they had terminated 50,000 instances of DRAGONBRIDGE activity throughout 2022, some of which contained pro-China views and content critical of the U.S.[77] These were not the only operations; at least three other APTs controlling over 2,000 social media accounts sought similar aims but were shut down by Twitter in October 2022.[78] Around this same time period, Meta disrupted a China-based network, potentially affiliated with or run by APT41, on Facebook that was attempting to stir conflict and discontent around hot-button issues like abortion and gun control before the 2022 midterms.[79] While the effectiveness of these operations were generally assessed as low by the various technology platforms who took down the disinformation content and accounts, the scope of the DRAGONBRIDGE campaign demonstrates that the CCP and its affiliates are pouring more money into disinformation operations than ever before.

Multiple hackers in APT41 were previously employed at Chengdu 404 Network Technology, a cybersecurity firm which created a “big data repository” for social media accounts of individuals of interest to the Chinese intelligence services.[80], [81] The fact that the same actors who worked on domestic surveillance and control technologies for the CCP later moved on to foreign disinformation operations at APT41 suggests that there is potential for an overlap in tactics and methodologies used in both foreign and domestic influence operations.

Americans Vulnerable to Chinese Information Campaigns

The groups of Americans particularly vulnerable to Chinese mis- and disinformation include Americans on the far-left of the political spectrum and members of the Chinese diaspora. Although there are diverse opinions under the banner of leftism, two variations of the term are state-centered leftism and populist leftism, both of which contain many adherents with positive views towards China — and, conversely, negative views towards the West.[82] For example, on the Reddit pages “r/communism” and “r/socialism,” with 227,000 and 420,000 members respectively from the global population posts regarding China are overwhelmingly positive. Both subreddits also contain a strong anti-voting sentiment, which is particularly disdainful of voting for moderate Democratic candidates and instead promotes organizing revolutionary activities.[83] Thus, CCP-sponsored mis- and disinformation regarding elections would likely be very effective in these groups.

The other group vulnerable to pro-CCP information operations are members of the Chinese diaspora. While homogenizing a group such as this is impossible, the CCP frequently attempts to use the Chinese diaspora through manipulative diplomatic power by stoking Chinese nationalism among members through mechanisms such as the UFWD and then encouraging diaspora members to push a positive view of China and the CCP.[84] This phenomenon occurred in Australia where Chinese billionaire and permanent Australian resident Huang Xiangmo indirectly bribed a rising star politician into a more pro-CCP position.[85] Huang was later exiled from Australia on national security grounds, but his influence over a popular politician serves as a warning against the long arm of the CCP.

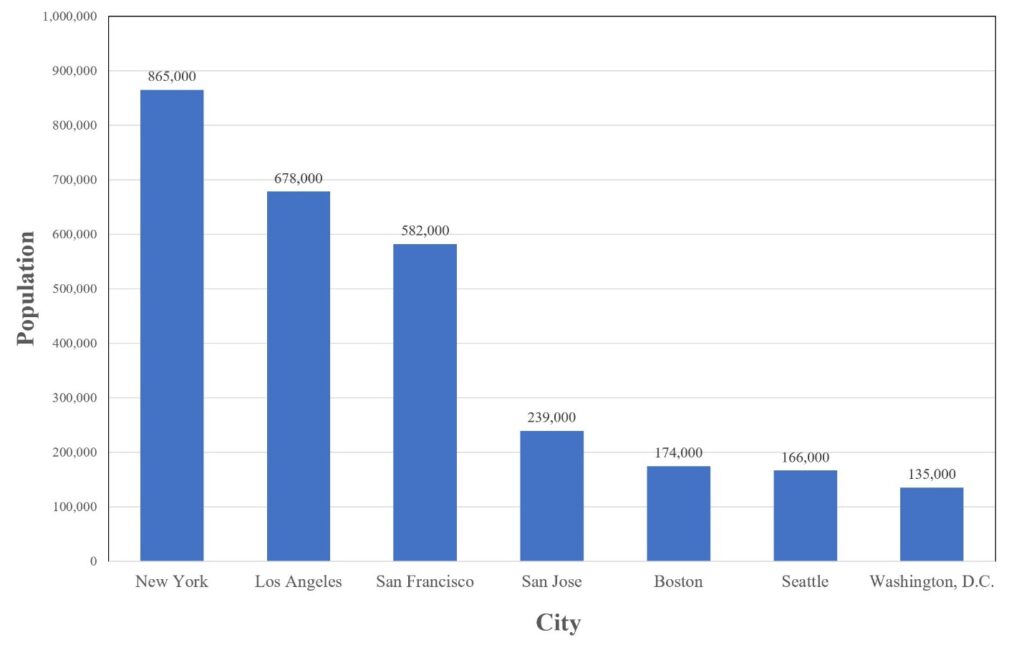

If Chinese mis- and disinformation operations targeted at the diaspora are successful, U.S. politicians running in congressional districts in which the Chinese diaspora represents a significant voting bloc may avoid professing harsh views regarding the CCP. Figure 7 illustrates the top U.S. metropolitan areas by Chinese population and suggests the areas that may have an extensive Chinese diaspora susceptible to these influence operations. This mis- and disinformation against the Chinese diaspora is made particularly impactful when it is paired with overseas coercion attempts by the CCP, a phenomenon just now beginning to be prosecuted in the United States. In October 2022, the U.S. Department of Justice charged six individuals with conspiring to act as illegal agents of the PRC.[86] U.S. authorities have also discovered networks of persons connected to the CCP who have attempted to influence the actions and speech of the Chinese diaspora through coercion, stalking, and other means, even including congressional candidates in these efforts.[87]

Figure 7 – Top U.S. Metropolitan Areas by Chinese Population (2019) [88]

Figure 7 – Top U.S. Metropolitan Areas by Chinese Population (2019) [88]

Lessons Learned from Taiwan

While the U.S. is subject to the highest amount of Chinese disinformation seeking to effect political behavior, Taiwan faces the highest volume of CCP disinformation.[89] In Taiwan, the Chinese regime has used mis- and disinformation tactics to boost the profiles of politicians friendly to the PRC and foment mistrust in the Taiwanese government.[90] Although the influx of falsified information during Taiwan’s 2020 election cycle did not result in victory for the CCP’s preferred candidate, the volume of false narratives pushed through Chinese disinformation channels on platforms such as PTT, a social news aggregation and discussion website in Taiwan similar to Reddit, has the potential to steadily erode Taiwanese democratic principles by widening divisions in society on issues like unification with China and undermining trust in democracy itself.[91], [92] Consistent with more general research on human reactions to disinformation, Doublethink Lab demonstrated that disinformation in Taiwan is more effective when it is emotionally triggering and can spread quickly through online channels.[93] One example of disinformation of this sort was the spread of rumors from a PRC content farm in Summer 2017 that the current Tsai administration was going to ban the burning of incense and the use of firecrackers over environmental concerns, sparking a 10,000 person strong protest against the suppression of religious and cultural traditions.[94] Another example is disinformation suggesting that the Taiwanese pension reforms in 2018 were going to be more severe and affect more people than officially announced.[95]

When it comes to combatting disinformation, it has been shown that immediate and transparent actions are best at countering the impact of disinformation.[96] In Taiwan, the civil society organization Taiwan FactCheck Center has delivered quick clarifications with broad coverage regarding issues in which disinformation from foreign actors is prominent to great effect.[97] In the U.S., social media platforms such as Meta employ third-party factcheckers certified by the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN), a subsidiary of the journalism research organization Poynter Institute.[98] However, data from the Pew Research Center shows that 42% of Americans believe that tech companies should not restrict false information online while 58% believe that the government should not limit online information.[99] In order to most effectively factcheck while maintaining American support, using a trusted organization such as the IFCN for factchecking, instead of third parties merely certified by the IFCN, could help increase the transparency factor.

Russian-Chinese Cooperation in Foreign Influence Campaigns

Russia and China are both leaders in the field of foreign influence campaigns. Whereas Russia is the more established power in this space with significant experience and a wide network of proxies, China is only beginning to employ its vast information infrastructure towards disinformation that affects elections. However, these two states are also acting together to accomplish shared goals. Since the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russian and Chinese state-owned or influenced news organizations have begun to promote each other’s coverage of the war; wolf warrior diplomats now frequently boost anti-NATO narratives, and Chinese censors allow Russian news to propagate far more freely in China than Western media.[100]

This cooperation on disinformation regarding Ukraine seems to have been remarkably easy to implement. For example, in 2019 during the Hong Kong pro-democracy protests, a few members of the far-right Ukrainian militia flew to Hong Kong to join the protests. Although these men were acting in an unofficial capacity, an altered version of this story has been widely spread within China since the start of the Russia-Ukraine war, stating that these militia members were part of a U.S.-funded demonstration campaign.[101] Due to the widespread proliferation of this story, searches associating Ukraine with Nazism have greatly increased in mainland China, in addition to similar narratives being pushed by pro-China politicians in Taiwan.[102]

The mutual support between Chinese and Russian information actors over the Ukraine issue is a culmination of a steadily increasing interconnectedness between the news outlets of both countries. Events such as a cooperation agreement between Voice of Russia and People’s Daily, signed in 2013, and a similar deal between Xinhua News Agency and RT in 2015 laid the groundwork for a friendly information environment between the two countries which mutually reinforces the disinformation spread by the other.[103]

Russia and China’s cooperation on disinformation surrounding Ukraine could potentially lead to a coordinated effort to exploit the economic difficulties and political tensions caused by the invasion to influence American elections. As the war drags on and nuclear tensions increase, the chorus of populist voices criticizing U.S. aid to Ukraine, from the right and the left grows.[104] Outlets from the far-right and far-left have bolstered the Russian conspiracy theory that the U.S. is funding the creation of bioweapons in Ukraine to threaten Russia.[105] Americans who prefer U.S. isolationism are particularly vulnerable to this disinformation, which can also bolster the campaigns of politicians who are friendly to Russia and China.

[1] National Intelligence Council. (2021, March 10). Foreign Threats to the 2020 US Federal Elections. https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/ICA-declass-16MAR21.pdf

[2] Cunningham, C. (2020, November 12). A Russian Federation Information Warfare Primer. University of Washington, The Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies.

[3] Select Committee on Intelligence United States Senate. (2019). Russian Active Measures Campaigns and Interference in the 2016 U.S. Election. Senate, Report 116. Vol. 4.

[4] Beuth, P., Biermann, K., Klingst, M., & Stark, H. (2017, May 12). Merkel and the Fancy Bear. Die Zeit.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Marten, K. (2020, July 7). The GRU, Yevgeny Prigozhin, and Russia’s Wagner Group: Malign Russian Actors and Possible U.S. Responses. Testimony before the Committee on Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Europe, Eurasia, Energy, and the Environment, United States House of Representatives.

[7] Isaac, M. & Wakabayashi, D. (2017, October 30). Russian Influence Reached 126 Million Through Facebook Alone. The New York Times.

[8] Heinrich, M. & MacSwan, A. (2022, November 7). Russia’s Prigozhin admits interfering in U.S. elections. Reuters.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Yablokov, I. (2022, June 10). Russian disinformation finds fertile ground in the West. Nature Human Behavior, 6, pgs. 766-767.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Dubow, B., Lucas, E., & Morris, J. (2021, December 2). Jabbed in the Back: Mapping Russian and Chinese Information Operations during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Center for European Policy Analysis.

[13] Frenkel, S. & Thompson, S.A. (2022, March 23). How Russia and Right-Wing Americans Converged on War in Ukraine. The New York Times.

[14] White, M. (2017, November 2). I started Occupy Wall Street. Russia tried to co-opt me. The Guardian.

[15] Pew Research Center. (2021, November 9). Outsider Left.

[16] Harris, S., Nakashima, E., Scherer, M., & Sullivan, S. (2020, February 21). Bernie Sanders brief by U.S. officials that Russia is trying to help is presidential campaign. The Washington Post.

[17] Rao, A. (2020, March 13). Bernie or Bust: the Sanders fans who will never vote for Biden. The Guardian.

[18] Pew Research Center. (2021, November 9). Outsider Left.

[19] Weaver, C. & Murphy, H. (2020, February 28). Sanders Hints the ‘Bernie Bros’ Could Be Russian Bots. Financial Times.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Isaac, M. & Wakabayashi, D., Russian Influence Reached 126 Million Through Facebook Alone. The New York Times.

[22] Hao, K. (2021, September 16). Troll farms reached 140 million Americans a month on Facebook before 2020 election, internal report shows. MIT Technology Review.

[23] Parlapiano, A. & Lee, J.C. (2018, February 16). The Propaganda Tools Used by Russians to Influence the 2016 Election. The New York Times.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Falconer, R. (2022, August 5). Meta shuts down Russian troll farm linked to sanctioned Putin ally. Axios.

[26] Doroshenko, L. & Lukito, J. (2021). Trollfare: Russia’s Disinformation Campaign During Military Conflict in Ukraine. University of Southern California, International Journal of Communications, 15.

[27] Brown, S. (2022, April 6). In Russia-Ukraine war, social media stokes ingenuity, disinformation. MIT Sloan.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Kowalski, A. (2022, June 8). Disinformation fight goes beyond Ukraine and its allies. Chatham House.

[30] Klepper, D. (2022, August 9). Russian disinformation spreading in new ways despite bans. Associated Press.

[31] Di Blasi, F. & Javadi, M. (2022, April 28). A pro-Russian bot network in the EU amplifies disinformation about the war in Ukraine. European Digital Media Observatory.

[32] Kowalski. Disinformation fight goes beyond Ukraine and its allies. Chatham House.

[33] News Wires. (2022, June 3). African Union head tells Putin Africans are ‘victims’ of Ukraine Conflict. France 24.

[34] Thomson Reuters. (2022). Glossary: Publicity Department of the Communist Party of China (CPCPD) (中共中央宣传部). Practical Law.

[35] Thomson Reuters. (2022). Glossary: Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) (国家互联网信息办公室). Practical Law.

[36] Bowe, A. (2018, August 4). China’s Overseas United Front Work: Background and Implications for the United States. U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission.

[37] Groot, G. (2018, April 24). The Rise and Rise of the United Front Work Department under Xi. The Jamestown Foundation, China Brief, 18(7).

[38] Doyon, J. (2019, December 17). The Strength of a Weak Organization: The Communist Youth League as a Path to Power in Post-Mao China. The China Quarterly, Cambridge University Press.

[39] Liao, X. & Tsai, W. (2021, September 16). Institutional Changes, Influences and Historical Junctures in the Communist Youth League of China. The China Quarterly, Cambridge University Press.

[40] Lau, M. (2022, May 20). Reshaping of China’s Communist Youth League gives insight into party resilience. South China Morning Post.

[41] Wood, P. (2020, January). China Seeks New Methods to Control Information Space. Foreign Military Studies Office, OE Watch, 10(1).

[42] Lin, B., Garafola, C.L., McClintock, B., Blank, J., Hornung, J.W., Schwindt, K., Moroney, J.D.P., Orner, P., Borrman, D., Denton, S.W., & Chambers, J. (2022). Competition in the Gray Zone: Countering China’s Coercion Against U.S. Allies and Partners in the Indo-Pacific. RAND Corporation, pg. 48.

[43] Dreyer, J.T. (2018, February 19). China’s United Front Strategy and Taiwan. University of Nottingham, Taiwan Studies Programme.

[44] Chen, W. (2017, October 5). Taiwanese identity crucial to facing threat. Taipei Times.

[45] China Index. (2022). Country Profiles: United States. Doublethink Lab.

[46] Mattis, P. (2012, October 19). China’s International Right to Speak. The Jamestown Foundation, China Brief, 12(20).

[47] Ibid.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Malekos Smith, Z. L. (2021, October 13). New Tail for China’s ‘Wolf Warrior’ diplomats. Center for Strategic and International Studies.

[50] Brandt, J. & Schafer, B. (2020, October 28). How China’s ‘wolf warrior’ diplomats use and abuse Twitter. Brookings Institution.

[51] Zhao Lijian (@zlj517). (2022, August 16). “Everyone needs a clear understanding of himself. So does a nation.” https://twitter.com/zlj517/status/1559530185686675457

[52] Alden, C. & Chan, K. (2021, June). Twitter and digital diplomacy: China and COVID-19. The London School of Economics and Political Science.

[53] Martin, P. (2021, October 22). Understanding Chinese “Wolf Warrior Diplomacy”. The National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR).

[54] Churchill, O. (2019, August 24). Chinese diplomat known for Twitter Tirades gets senior foreign ministry job. South China Morning Post.

[55] Palmer, A. W. (2021, July 7). The man behind China’s aggressive New Voice. The New York Times.

[56] Martin, P. Understanding Chinese “Wolf Warrior Diplomacy”. NBR.

[57] Tian, Y. L. (2022, September 29). China signals no let-up in its aggressive diplomacy under Xi. Reuters.

[58] Ruwitch, J. (2023, January 12). A ‘wolf warrior’ is sidelined, as China softens its approach on the world stage. NPR.

[59] Goldenziel, J. (2022, May 19). The Disinformation Governance Board is dead. Here’s the right way to fight disinformation. Forbes.

[60] Mozur, P., Zhong, R., Krolik, A., Aufrichtig, A., & Morgan, N. (2021, December 13). How Beijing Influences the Influencers. The New York Times.

[61] The Grayzone. About. https://thegrayzone.com/about/

[62] Ibid.

[63] Berletic, B. (2021, October 18). Behind the ‘Uyghur Tribunal’, US Govt-backed separatist theater to escalate conflict with China. The Grayzone.

[64] Maté, A. (2021, December 6). War in Ukraine? NATO expansion drives conflict with Russia. The Grayzone.

[65] Maté, A. (2020, December 4). After Trump leaves, US and Israeli aggression against Iran remains. The Grayzone.

[66] Norton, B. (2021, November 24). Venezuela’s Socialists win elections in landslide – so US tries to discredit them. The Grayzone.

[67] Cohen, D. (2019, August 18). Behind a made-for-TV Hong Kong protest narrative, Washington is backing nativism and mob violence. The Grayzone.

[68] The Grayzone. (2021, March 30). Max Blumenthal debunks US accusation of China’s ‘genocide’ against Uighurs. YouTube. 28:51 duration. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qZkxaEC1xjY&ab_channel=TheGrayzone

[69] Xin, L. (2020, April 25). Not anti-US, but speak for betrayed Americans: The Grayzone founder. Global Times.

[70] Zhao Lijian (@zlj517). (2019, December 30). “Claims that China detained millions of Uyghur Muslims are based largely on 2 studies…” https://twitter.com/zlj517/status/1211621187224141824?lang=en

[71] Meers, Z., Wallis, J., & Zhang, A. (2021, March 30). Strange bedfellows on Xinjiang: The CCP, fringe media and US social media platforms. Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI).

[72] Qing, K. G., & Shiffman, J. (2015, November 2). Exposed: China’s Covert Global Radio Network. Reuters.

[73] U.S. Department of Justice. (2021, December 16). Exhibit A to Registration Statement Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended. https://efile.fara.gov/docs/7059-Exhibit-AB-20211216-2.pdf

[74] U.S. Department of Justice. (2022, January 13). Supplemental Statement Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended. https://efile.fara.gov/docs/7059-Supplemental-Statement-20220113-1.pdf

[75] California Secretary of State. (2021, December 6). Secretary of State Certificate of Dissolution. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1pmhVCumGOTEyyQkSbf8hpU__dBl1lEKb/view?usp=sharing

[76] Mandiant Intelligence. (2022, October 26). Pro-PRC DRAGONBRIDGE Influence Campaign Leverages New TTPs to Aggressively Target U.S. Interests, Including Midterm Elections.

[77] Butler, Z. & Taege, J. (2023, January 26). Over 50,000 instances of DRAGONBRIDGE activity disrupted in 2022. Google.

[78] Menn, J., Merrill, J.B., & Nix, N. (2022, November 1). MAGA porn, hate for Trump: China-based accounts stoke division. The Washington Post.

[79] Nix, N. (2022, September 27) Facebook parent dismantles China-based network targeting American users. The Washington Post.

[80] Intrusiontruth. (2022, July 22). Chengdu 404. https://intrusiontruth.wordpress.com/2022/07/22/chengdu-404/

[81] U.S. Cyber Command. (2022). SECTION 2: CHINA’S CYBER CAPABILITIES: WARFARE, ESPIONAGE, AND IMPLICATIONS FOR THE UNITED STATES. Pg. 456.

[82] Gui, Y., Huang, R., & Ding, Y. (2020). Three faces of the online leftists: An exploratory study based on case observations and big-data analysis. Chinese Journal of Sociology, 6(1), 67–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057150×19896537

[83] u/Patterson9191717. “To defeat the far right, we should oppose voting for Democrats & fight for an independent working-class political party that puts forward an alternative vision for society that can speak to the despair of working people”. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/socialism/comments/xj62zj/to_defeat_the_far_right_we_should_oppose_voting/

[84] Wong, A. (2022). The diaspora and China’s Foreign Influence Activities. Wilson Center.

[85] Searight, A. (2020, May 8). Countering China’s Influence Operations: Lessons from Australia. Center for Strategic and International Studies.

[86] U.S. Attorney’s Office, Eastern District of New York. (2022, October 20). Six Individuals Charged with Conspiring to Act as Illegal Agents of the People’s Republic of China. Department of Justice.

[87] Rotella, S. (2022, March 17). DOJ Charges Defendants With Harassing and Spying On Americans for Beijing. ProPublica.

[88] Budiman, A. (2021, April 29). Chinese in the U.S. Fact Sheet. Pew Research Center.

[89] Lührmann, A., Gastaldi, L., Grahn, S., Lindberg, S. I., Maxwell, L., Mechkova, V., Morgan, R., Stepanova, N., & Pillai, S. (2019). V-Dem Annual Democracy Report 2019: Democracy Facing Global Challenges. V-Dem Institute, University of Gothenburg.

[90] Corcoran, C., Crowley, B. J., & Davis, R. (2019, May). Disinformation Threat Watch: The Disinformation Landscape in East Asia and Implications for US Policy. Harvard Kennedy School, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs.

[91] Kao, S. W., Lee, L. M., Shen, P., Tseng, P., & Wu, M. (2020, October 24). Deafening Whispers: China’s Information Operation and Taiwan’s 2020 Election. Doublethink Lab.

[92] Harold, S.W., Beauchamp-Mustafaga, N., & Hornung, J.W. (2021). Chinese Disinformation Efforts on Social Media. RAND Corporation, pp. 67-69.

[93] Chen, Y. & Tseng, P. (2021, May 6). An analysis on the impact of false information on Taiwanese voters: Exit poll results from Taiwan’s 2020 presidential and legislative elections. Doublethink Lab.

[94] Harold, et. al., Chinese Disinformation Efforts on Social Media, pg. 68.

[95] Ibid.

[96] Kao, S., et al. Deafening Whispers. Doublethink Lab, pg. 86.

[97] Ibid.

[98] Meta. (2021, June 1). How Meta’s third-party fact-checking program works.

[99] Schaeffer, K. (2020, May 29). Fast facts about American’s views of social media companies as Trump-Twitter dispute grows. Pew Research Center.

[100] U.S. Department of State. (2022, May 2). People’s Republic of China Efforts to Amplify the Kremlin’s Voice on Ukraine.

[101] Yu, J. (2022, March 31). Analysis: How Ukraine has been Nazified in the Chinese information space? Doublethink Lab.

[102] Ibid.

[103] Bandurski, D. (2022, March 11). China and Russia are joining forces to spread disinformation. The Brookings Institution.

[104] Dutkiewicz, J. (2022, July 4). Why the U.S. Far Right and Far Left Have Aligned Against Helping Ukraine. Foreign Policy.

[105] Seldin, J. (2022, March 10). US Fears Russian Disinformation About Ukraine Bioweapons Gaining Traction. VOA News.