Co-authored by Ty Gribble and Jacquie Moss

1: The Problem

“Fake News” has become a highly discussed phenomenon, sparking concerns that society at large is awash with disinformation. However, empirical evidence suggests that fake news is a minuscule part of Americans’ daily media consumption (Allen et al. 2020, Nelson and Taneja 2018). Furthermore, most users can generally distinguish credible websites from unreliable ones (Dias et al 2020). These findings suggest that disinformation is a different threat than previously understood. We argue that credible-looking sites with misleading information sow doubt about the urgency of climate change. This sort of seemingly legitimate difference of perspectives may be more problematic because of its broader appeal.

As people browse the Internet, they use mental shortcuts, such as visual design and professional tone, to determine a source’s credibility. People have come to expect certain qualities from a trustworthy news site, such as a well-structured and minimal design presentation, objective and authoritative language, and well-researched content using data-backed charts and quotes from subject matter experts. People’s reliance on these cognitive shortcuts – or heuristics – may be mostly accurate, but they are imperfect. Bad actors can weaponize expectations about credibility to make disinformation appear as credible information. This blog post explores how some climate-related misinformation passes as credible by adopting stylistic and substantive qualities associated with credibility.

2: Examples

2.1: Credible Information

ABC News is one of America’s most trusted news sources, behind only the Weather Channel and PBS. Thus, the ABC News website is a reasonable place to consider how people develop heuristics and hone expectations about what a credible news site looks like.

This image shows the home page for ABC News on June 9, 2024. It has a simple white background and coherent structure, with headings for different topics, allowing easy site navigation. The most pressing ongoing coverage exists above the rest of the home page, accented with a red “Live Updates.” Next, concise headlines are presented with an editorial hierarchy. These elements are important to readers, who decide how pleasing a website is in milliseconds (Fogg et al 2003, Billard and Moran 2023). Ending a headline with “Official” or “live updates” conforms with expectations of official sources and an active newsroom, which are important in perceiving source credibility (Preston et al 2021).

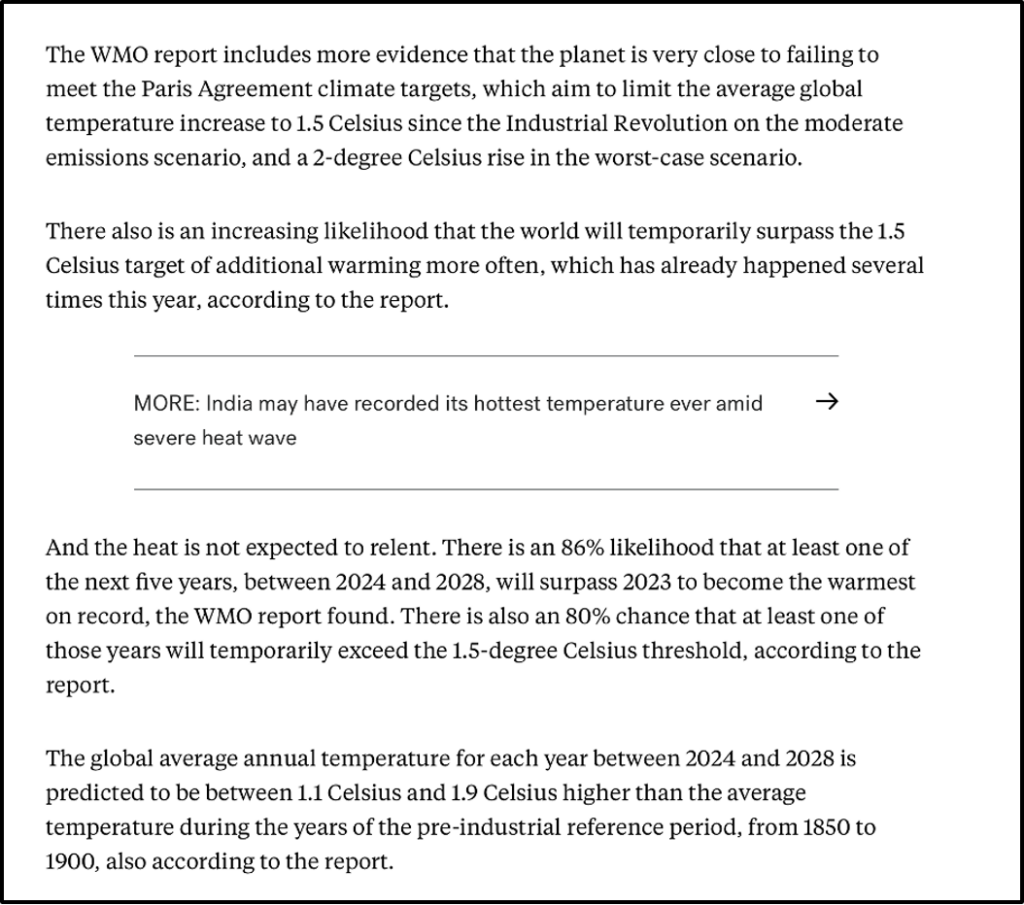

We then take an article by ABC News on World Environment Day to examine climate-specific information. The reference to climate officials and 12 months of record high temperatures conveys that experts on the subject are making a credible warning. The authors understand the gravity of the subject, but they do not sensationalize the issue. Instead, the body of the text is full of statistics and quotes from official sources, as seen below:

ABC News exemplifies what people expect credible news to look like. They expect trustworthy news sources to be minimally designed, communicate with a neutral tone, and substantiate claims with objective data.

2.2 Non-Credible Information

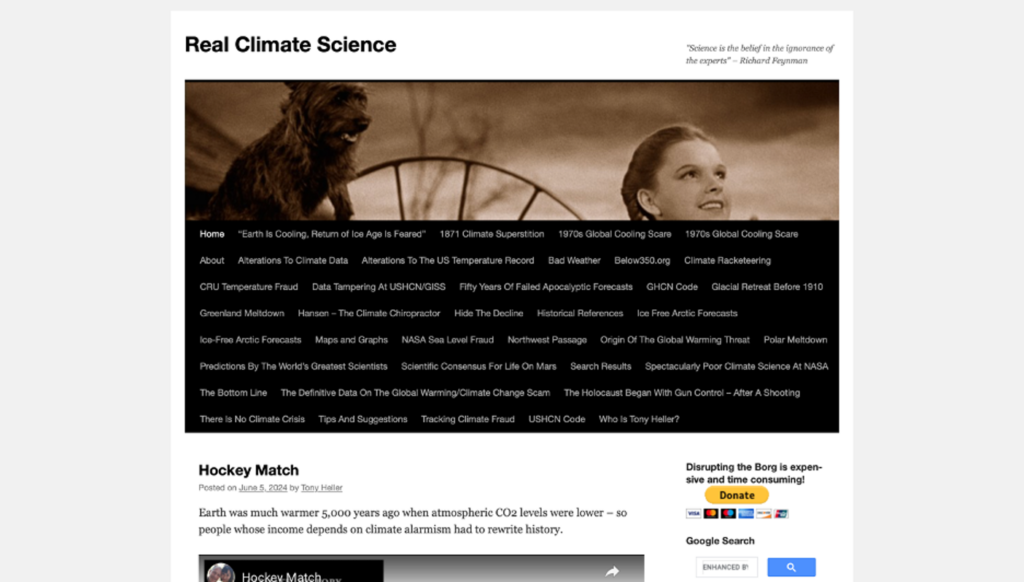

We briefly show news that is conspicuously fake as an example to contrast what is perceived as real to what is fake. We use “Real Climate Science” as an example. The site is full of incorrect claims, most of them about the alleged inconsistencies of climate science, with the aim of proving that it is a hoax.

Starting with visual design, the site does not fit the width of a computer screen. Its headings are eclectic, with no real organization or hierarchy. The tone is also clearly unprofessional, with the website calling Climate Change a “scam” and claiming that warnings about CO2 levels were contrived by “people whose income depends on climate alarmism.”

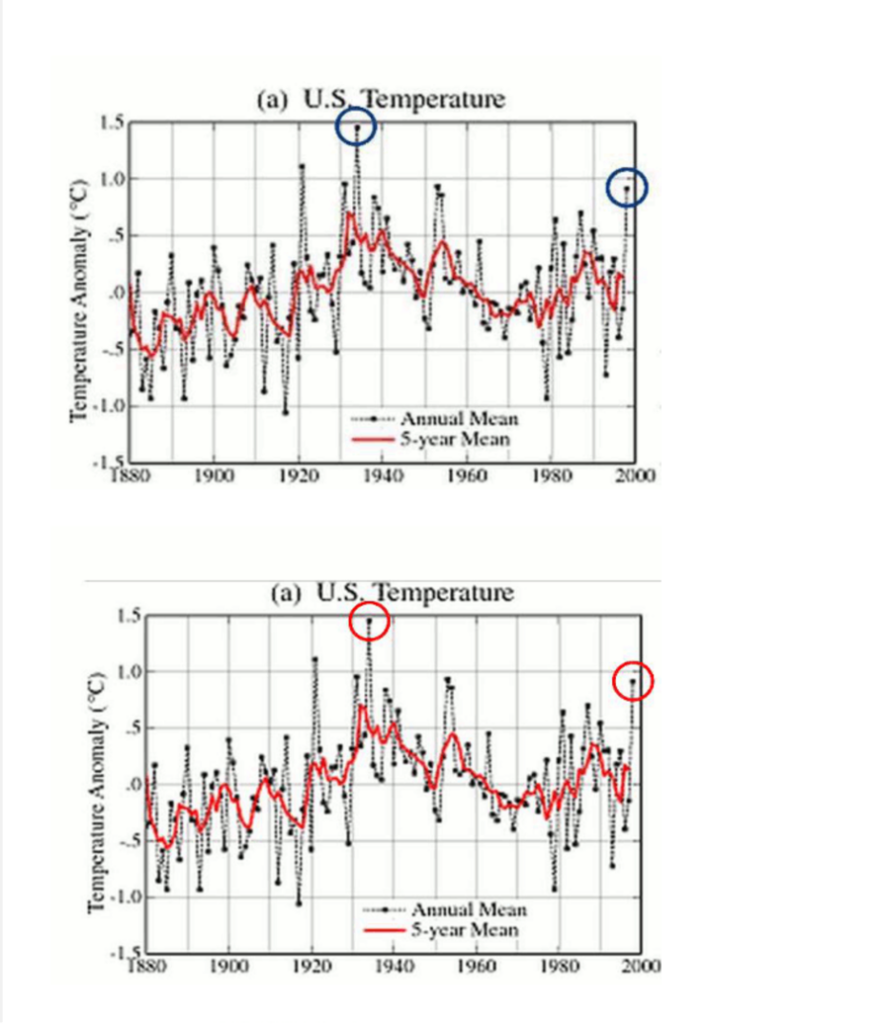

However, the site does attempt to appear credible. On the page “Maps and Graphs,” plenty of figures are used to deny climate change. Given the site’s other shortcomings, it is unlikely that this will single-handedly change perceptions.

2.3: Credible-Looking Misinformation

To understand what credible climate misinformation looks like, it is important to reference what people think about climate change. While most believe in climate change, fewer believe it is a priority: Pew Research survey data indicates it ranks 17th of 21 national issues for Americans. Pew Research explains that the issue salience of climate change relies heavily on partisanship: “For Democrats, it falls in the top half of priority issues, and 59% call it a top priority. By comparison, among Republicans, it ranks second to last, and just 13% describe it as a top priority.”

Pew Research interviewed Republican and Republican-leaning voters to capture the scope of their beliefs about climate change and the environment. The key takeaway: Republicans support some climate policies but are concerned about the costs necessary to achieve them. Thus, credible-looking misinformation will magnify fears of the tradeoffs required to combat climate change.

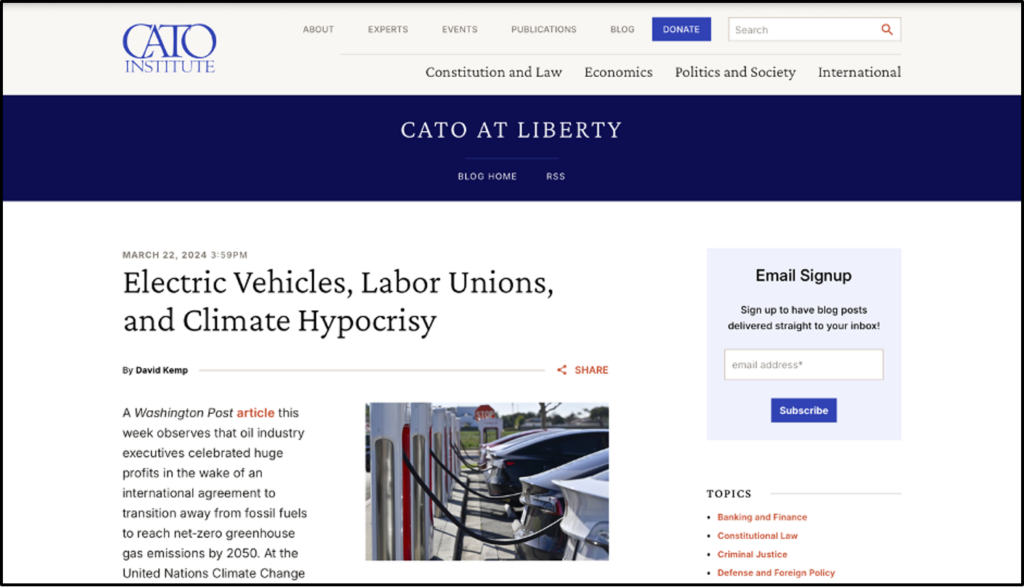

With this information in mind, we looked for an example that did not explicitly deny that climate change is occurring but rather downplayed its significance. We used an article from the CATO Institute because it activates many heuristics that make people perceive it as credible. Paired with misleading claims about climate change, this approach may lead people to adopt misinformed attitudes about the urgency of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Starting with visual design, we can quickly point out similarities between ABC News and the CATO Institute. The top headings are neatly arranged and suggest some kind of hierarchy. The website uses a clean white background, which people find simple to read and understand. The search function improves the website’s navigability. The tone is less formal, referencing “climate hypocrisy” in the headline, but not so negatively charged as to put a discerning reader on alert. Familiar sights like email signups and links to other articles reinforce the same expectations for credible media.

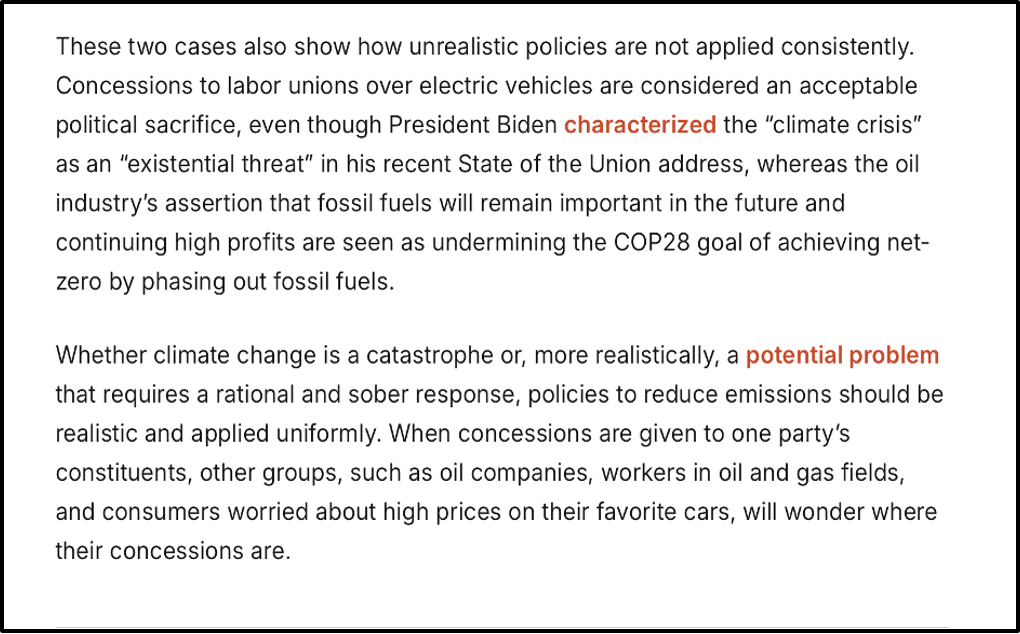

The author refrains from making any claims about conspiracies and hoaxes. Instead, they make smaller and ostensibly more plausible claims about climate change. For example, “climate change is more realistically a potential problem which requires a rational and sober response…” This sentence perfectly downplays the threat of climate change and positions the author as reasonable and measured. By implicitly arguing that climate change is overhyped, the issue is framed as a minor one. No science is denied, but the importance of climate change in the reader’s mind is likely diminished. No one would dispute that it is good to respond rationally and soberly to problems or that it is good to be realistic with solutions. The author positions the argument as merely asking questions about the issue, not undermining its legitimacy. This is a key distinguishing factor between credible information and misinformation. Actual credible information makes claims that are substantiated by evidence, whereas credible-looking misinformation attempts to sow doubt through questioning.

3: Conclusions and Implications

Climate change disinformation is not just denialism and conspiracy theories. Instead, more widespread and problematic are articles that sow doubt or downplay the urgency of climate change. These articles are perceived as credible because they come from websites that employ the credibility heuristics of well-respected news sources.

The exploitation of credibility heuristics to undermine climate change messaging suggests how important it is for the reader to look past the design to assess the content. This entails switching from a passive consumer to a critical thinker. Project Mizaru’s preliminary findings suggest that deliberative (i.e., critical or analytical) thinking may be one of the most reliable ways to overcome the influence of partisan ideology. Several studies find that when people shift into “slow thinking” mode, there are fewer mistakes in discerning truth from falsehoods (Bago et al 2020, Pennycook et al 2019, Sindermann et al 2021).

You might wonder about the role of interventions to correct misleading information. The literature indicates that corrective interventions, such as fact-checking, debunking, and inoculation, may backfire (Brashier et al 2021, Dias et al 2020,Garret and Weeks 2012). Efforts to publicize corrections and offer a counter-narrative are risky. Fact-checkers may contribute to repetition and familiarity to debunk false claims because repeated exposure makes falsehoods more believable (Thorson 16, Lutzke et al 2019).

Studies have found that the most effective interventions are those that encourage people to think for themselves, likely because they shift people into critical thinking (i.e., slow) mode. Examples of these types of interventions include nudging people to think about accuracy (Pennycook et al., 2019) or encouraging people to consult other resources to confirm claims (Donovan and Rapp, 2020).

4: Acknowledgements

Thank you to Isabella Sherwood, Jonathan Bardin, David Tran, and Drew Wessels for helping to get this article off the ground!

5: References

Bago, Bence, David G Rand, and Gordon Pennycook. 2020. “Fake News, Fast and Slow: Deliberation Reduces Belief in False (but Not True) News Headlines.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 149(8): 1608–13.

Billard, Thomas J, and Rachel E. Moran. 2023. “Designing Trust: Design Style, Political Ideology, and Trust in ‘Fake’ News Websites.” Digital Journalism 11(3): 519–46. doi:10.1080/21670811.2022.2087098.

Brashier, Nadia M., Gordon Pennycook, Adam J. Berinsky, and David G. Rand. 2021. “Timing Matters When Correcting Fake News.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118(5): e2020043118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2020043118.

Corner, Adam, Ezra Markowitz, and Nick Pidgeon. 2014. “Public Engagement with Climate Change: The Role of Human Values.” WIREs Climate Change 5(3): 411–22. doi:10.1002/wcc.269.

Dias, Nicholas, Gordon Pennycook, and David G. Rand. 2020. “Emphasizing Publishers Does Not Effectively Reduce Susceptibility to Misinformation on Social Media.” Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review 1(1). doi:10.37016/mr-2020-001.

Donovan, Amalia M., and David N. Rapp. 2020. “Look It up: Online Search Reduces the Problematic Effects of Exposures to Inaccuracies.” Memory & Cognition 48(7): 1128–45. doi:10.3758/s13421-020-01047-z.

Feldman, Lauren, and P. Sol Hart. 2018. “Is There Any Hope? How Climate Change News Imagery and Text Influence Audience Emotions and Support for Climate Mitigation Policies.” Risk Analysis 38(3): 585–602. doi:10.1111/risa.12868.

Fogg, B. J., Cathy Soohoo, David R. Danielson, Leslie Marable, Julianne Stanford, and Ellen R. Tauber. 2003. “How Do Users Evaluate the Credibility of Web Sites?: A Study with over 2,500 Participants.” In Proceedings of the 2003 Conference on Designing for User Experiences, San Francisco California: ACM, 1–15. doi:10.1145/997078.997097.

Garrett, R. Kelly, and Brian E. Weeks. 2013. “The Promise and Peril of Real-Time Corrections to Political Misperceptions.” In Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, San Antonio Texas USA: ACM, 1047–58. doi:10.1145/2441776.2441895.

Lutzke, Lauren, Caitlin Drummond, Paul Slovic, and Joseph Árvai. 2019. “Priming Critical Thinking: Simple Interventions Limit the Influence of Fake News about Climate Change on Facebook.” Global Environmental Change58: 101964. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.101964.

Nelson, Jacob L, and Harsh Taneja. 2018. “The Small, Disloyal Fake News Audience: The Role of Audience Availability in Fake News Consumption.” New Media & Society 20(10): 3720–37. doi:10.1177/1461444818758715.

Pennycook, Gordon, Jonathon McPhetres, Yunhao Zhang, Jackson G. Lu, and David G. Rand. 2020. “Fighting COVID-19 Misinformation on Social Media: Experimental Evidence for a Scalable Accuracy-Nudge Intervention.” Psychological Science 31(7): 770–80. doi:10.1177/0956797620939054.

Pennycook, Gordon, and David G. Rand. 2019. “Lazy, Not Biased: Susceptibility to Partisan Fake News Is Better Explained by Lack of Reasoning than by Motivated Reasoning.” Cognition 188: 39–50. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2018.06.011.

Preston, Stephanie, Anthony Anderson, David J. Robertson, Mark P. Shephard, and Narisong Huhe. 2021. “Detecting Fake News on Facebook: The Role of Emotional Intelligence” ed. Pablo Fernández-Berrocal. PLOS ONE 16(3): e0246757. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0246757.

Sindermann, Cornelia, Helena Sophia Schmitt, Dmitri Rozgonjuk, Jon D. Elhai, and Christian Montag. 2021. “The Evaluation of Fake and True News: On the Role of Intelligence, Personality, Interpersonal Trust, Ideological Attitudes, and News Consumption.” Heliyon 7(3): e06503. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06503.

Thorson, Emily. 2016. “Belief Echoes: The Persistent Effects of Corrected Misinformation.” Political Communication33(3): 460–80. doi:10.1080/10584609.2015.1102187.

Wolff, Laura, and Monika Taddicken. 2022. “Disinforming the Unbiased: How Online Users Experience and Cope with Dissonance after Climate Change Disinformation Exposure.” New Media & Society: 146144482210901. doi:10.1177/14614448221090194.